On October 22, Sterling Associates, Inc.—a fine arts and estates auction firm in Closter, New Jersey—sold two vampire hunting kits: a “Vampire Hunting Kit in Coffin Box” (Lot 337) for US$9,000 and “Vampire Hunting Kit in Hand Painted Box” (Lot 338) for US$6,500 from its Danse Macabre collection. Both were listed as “19th Century European Vampire hunting kit[s]”.

Many “19th century” vampire killing kits are sold through auction houses and purchased by museums or private buyers. They were apparently sold to travellers vacationing through Europe, as a superstitious novelty item. But I’m here to tell you that whoever’s bought these should’ve held onto their money. Here’s why:

#6. They’re Not Properly Authenticated

I found out about the Sterling Associates sale through Sophie Jane Evans’ Daily Mail article, “Worried That Dracula Is Headed Your Way? Vampire-Slaying Kit from 1800s Complete with Wooden Stakes, Crucifixes and Vials of Holy Water Goes Up for Sale (You Might Want to Add Garlic Just in Case)” (October 19, 2014) distribution on Facebook.

Like many journalists covering “antique” vampire killing kits, she took their alleged age at face value. Few bother discussing authenticity with dealers. But I do. I contacted Sterling Associates via Facebook, shortly before the items went on sale: “What evidence have you seen of the kit’s authenticity? That is, it being manufactured in the 19th century?” Their response?

We believe that the boxes and the elements contained in the boxes to be 19th Century. We are not experts on Vampire-Slaying kits.

We are unaware of any manufacturer that fabricates these boxes so the amount of research and the ability to research is limited.

When they were assembled and if they were ever used to kill vampires is beyond our expertise.

Dealers aside, what about museums? Surely they’re much more cautious. I put that to the test by interviewing Ripley Believe It or Not’s! Vice President of Exhibits and Archives in my Vampirologist post, “Q & A with Edward Meyer” (October 7, 2011), the man responsible for the largest collection of “19th century” vampire killing kits in the world. According to a Ripley’s 2009 press release (no longer available online):

The kits were acquired by people in preparation of possibly meeting a vampire during their international travels to Eastern Europe and their usage dates back to the mid-1800s. Most were created in the Boston area and were available by mail order.

And:

The kits were purchased by wealthy Americans headed to Eastern Europe – Transylvania then, Romania now. Travelers brought back terrifying tales of vampires with them from the region – well before Dracula was brought to life by Bram Stoker.

I asked Meyer a series of questions about their age. How had they been authenticated?

One of the key elements in a vampire killing kit is a pistol. Pistols can easily be dated by style, and maker. Some of the guns actually have dates an initials on them..From a study of several kits it is obvious some are older than others, but the guns typically come from the 1840s-50s

Had he seen any of the Boston mail orders? “No.” Did he have—or was he aware—of any 19th century documentation confirming their age? “No, we have nothing any earlier than 1990 mentioning their existence.” Did he know who any of the “wealthy Americans” were? “No one specifically” and so on. Notice a pattern?

Let’s try video evidence on for size. Here’s a YouTube video called “Vampire Killing Kits,” uploaded by Buck Wolf on January 10, 2010. It depicts Meredith Woerner examining a vampire killing kit “made in the mid 1800s” displayed at Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, Times Square, New York.

You’ll also see Michael Hirsch, the museum’s president, confirm the kit was “produced in the 1850s, and it was used for travellers if they were heading into Eastern Europe.”

[su_youtube url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=34cLAYp_DqY”]

Looks convincing, doesn’t it? However, as I mentioned in my Vampirologist blog post, “Buyers Beware!” (December 16, 2011), Woerner isn’t an antiquarian: she’s the author of a tongue-in-cheek vampire “field guide” called Vampire Taxonomy: Identifying and Interacting with the Modern-Day Bloodsucker (2009). Also, notice that she’s not actually examining the kit, but merely describing its contents.

Hirsch isn’t a qualified antiquarian, either. His LinkedIn profile reveals he specialises in “P&L Analysis/Management, Staff Motivation, Customized Best Practice Sales Techniques, Accelerated Expense Reduction, Internal Labor Analysis, Brand Leveraging/Building, Traditional and Digital Marketing Practices.”

Caveat emptor, indeed. If you want to bid on a “19th century” vampire killing kit, always ask the dealer how they’ve verified the kit’s age. Ask for supporting documentation. If you see one of these things displayed in a museum, ask similar questions. Though it’s counter-intuitive, don’t presume “19th century” means the kit was manufactured during that era.

Consider what Meyer told me during the “Q & A” interview; he knew “of no hard evidence to confirm where or when any of these items were made. As I stated before the date of the guns is the only thing you can confirm with confidence…..” If you’re after a genuine antique, you’ll need more than a plausible backstory and antique components to verify these beauties.

But what if you don’t have time to double-check whether a “19th century” vampire killing kit’s been properly authenticated? They’re being auctioned! They’re only available for a limited time! Even Meyer’s partially determined their value by supposed scarcity, “they are very rare, so they are a perfect museum artifact for Ripley’s.” Yeah, about that…

#5. They’re Not as “Rare” as You’d Think

Let’s use Ripley’s collection as an example. Lauren Davis’ io9 article, “Ripley’s Has Authentic Vampire Killing Kits for Every Taste” (December 7, 2009) reveals, “The Ripley’s collection, acquired by Ripley’s VP Edward Meyer, contains 30 authentic vampire killing kits, 26 of which are currently on display in eight Ripley’s museums.”

The figure’s confirmed by Ripley’s press release, “Vampires Beware: Ripley’s Believe It or Not! Owns the World’s Largest Collection of Authentic Vampire Killing Kits” (December 4, 2009):

Each kit in the Ripley’s collection was acquired by Edward Meyer, VP of Exhibits and Archives for the company. He recently acquired two more vampire killing kits, raising the number in the collection to 30. According to Meyer, the kits owned by Ripley are the only ones on public display in the country – the rest are in private collections.

“Vampire kits are very rare,” said Meyer. “There are maybe a handful of them outside of Ripley’s and we’d like to acquire those as well.” Meyer keeps an eye out for them at auction, on eBay and at antique shops in the South.

“They are very popular exhibits at our museums, especially now that there is so much interest in vampires in the media,” said Meyer.

Not a huge number, but not quite “one of a kind,” either—and the authenticity of these kits relies on Meyer’s liberal definition of “authentic”: they’re equipt with 19th century pistols. Even so, there’s plenty more “19th century” vampire killing kits out there.

The Spooky Land website’s done a brilliant job cataloguing vampire killing kits on their “Vampire Hunter Kit Gallery” page and interlacing links. The page’s sidebar also features 26 kits and a separate page for Ripley’s collection. However, as The BS Historian notes in their blog post, “Towards a Typology of Vampire Killing Kits” (October 2, 2010):

As you can see from Spooky Land’s attempt to classify and categorise VKKs, it is a daunting task, as no two kits are identical, and very few are even similar, despite the precisely-worded (“Blomberg”) label that many they share.

We’ll look into “Blomberg” later. In the meantime, if the Spooky Land site’s got you questioning the rarity of Meyer’s kits, wait till you find out how many Jonathan Ferguson’s tracked down. Ferguson, Curator of Firearms at the Royal Armouries Museum, Leeds—also an “antique” vampire killing kits expert—shared his findings in a guest post for D.A. Lascelles’ blog, Lurking Musings, “Vampire Killing Kits – Real or Fake?” (March 20, 2014):

One thing we know for sure is that they are not rare. So far, I have documented the existence of 100 kits that either purport, or appear to be, real. What do we mean by ‘real’? Well, ‘real’ can be a tricky concept, but most would probably suggest that it means ‘old’. Some might also say that it would include genuine purpose, as in kits created to actually slay vampires. As all evidence points to an American or western European origin some time in the twentieth century, it’s unlikely that they were made by, or for, believers in vampires.

Considering the kits’ diversity, how do we gauge “rareness” if no single model serves as a baseline? They’re not 1968 Dodge Chargers; they haven’t rolled off an assembly line. We can’t even classify them as “limited editions” if there’s no reliable consistency between them. For all we know, they could’ve been made by one, few or many different people over various periods of time. Without efforts made to properly authenticate their age and backstories, we have no idea—and we’ll never know.

The “created in the Boston area and were available by mail order” line Ripley’s expects us to swallow—one that its Vice President of Exhibits and Archives has zero evidence for—is the closest gauge we have to rarity. That, and the “Blomberg” name. Does it hold the key?

The mysterious Blomberg—Prof. Ernst Blomberg—is a name often associated with the kits. His name appears on labels and sometimes accompanying literature. In fact, the Spooky Land site divides its primary kit coverage between “Kits Containing Blomberg Elements” and “Non-Blomberg Kits,” on its massive “Regarding Ernst Blomberg” page.

I asked Meyer about Blomberg during our “Q & A” session, too. Did he know anything about him? Was he able to verify Blomberg’s connection to the kits? “Only what I have read in popular reports..there is a fair bit of info available by googling his name…” and “Personally? I haven’t,” he said.

With no evidence for their Boston manufacture—or evidence of “Prof. Ernst Blomberg’s” connection to the kits—it’s fair to suggest, the kits may’ve originated from a common source (see: #3), at best, but their diversity and lack of consistency indicates a copycat “cash-in” trade’s much more likely.

In fact, their frequent auction appearances undermine their “very rare” status—especially in the wake of media coverage discussing exorbitant sums they’re sold for. For instance, Antique Trader covered the sale of a vampire killing kit from the Jimmy Pippen estate in its article, “Bidder Sinks Fangs into Vampire Killing Kit for $14,850” (October 24, 2008).

Across the pond, a BBC News article, “‘Vampire-Slaying Kit’ Bought by Royal Armouries Museum” (June 25, 2012) revealed the Royal Armouries Museum, Leeds, actually paid £7,500 for their kit at a North Yorkshire auction. The kit purchased wasn’t even the only one from the same collection. As Tom Swain notes in his Leeds Northern & Yorkshire Voice article, “How to Kill a Vampire: The Real Life Slayer Kit of Leeds” (April 25, 2013):

But before appearing in auction, the kit had been owned by a collector of the occult, and a resident of Leeds. Though his identity remains unknown, he was 93 when he died, and left three vampire kits to a daughter-in-law – just one was put up for auction. Another was sold privately, and the third was kept by the family.

These “very rare” kits turn up on TV, too. The debut episode of Auction Kings, “Vampire Hunting Kit/Meteorite” (S1E1; October 26, 2010) features Edwin, an antique weapons collector, who brings a “very rare” kit to the show’s star, Paul Brown, who runs Gallery 63, a consignment auction house in Atlanta. The kit’s later sold to a telephone bidder for US$12,000.

[su_youtube url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pk_1t3jJmsE”]

We’ll deal with another kit’s TV appearance later, but first, I think it’s safe to ditch the “very rare” tag. There’s too many to justify that label, so let’s move onto another question: if they’re sold and bought for thousands of dollars—and obviously not genuine antiques—what the hell are they? I’m glad you asked…

#4. They’re Composites—Genuine Antiques Paired with Artificially-Aged Items

The “Vampire Killing Kit,” above, is housed at the Mercer Museum, Doylestown, Pa. Edward Ohlbaum’s Philadelphia Inquirer article, “Promoting Bucks County as a Destination, Not a Side Trip” (June 10, 1990) mentions the kit “was donated in 1989, said an official of the museum, which was built by [Henry C.] Mercer to house his collection of early American tools.”

Four years ago, I emailed Cory Amsler—the museum’s Vice President, Collections and Interpretation—asking whether their kit had been authenticated. I published his response in my Diary of an Amateur Vampirologist blog post, “Vampire Killing Kit Update!” (August 5, 2010):

It is believed to be one of the compilations of both historical items and “made up” artifacts that found its way into the antiques market sometime in the 1970s or 1980s. We had some portions of it analyzed in the labs of the Winterthur Museum and learned that the “silver” bullets are actually pewter (not a surprise given their lack of tarnish) and that the paper is of 20th century vintage that has been artificially “aged.” We use it currently to contrast traditional and contemporary vampire “lore,” help interpret the origins of some vampire beliefs, and to demonstrate the use of scientific methodologies in authenticating artifacts.

Two years ago, Amsler resurfaced in J.D. Mullane’s phillyBurbs.com article, “In Doylestown, a Kit to Kill Vampires” (October 28, 2012, 3:00 a.m.; updated November 1, 2013, 6:01 p.m.):

“When people return here to visit, and they bring someone, they say, ‘Oh, you’ve got to see the vampire killing kit,’ ” said Cory Amsler, the museum’s vice president for collections and interpretations.

Is it real?

“When we acquired the kit, we hadn’t seen anything quite like it,” Amsler said. “Obviously, many of the objects were period to the 1800s — percussion cap pistol, the bullet mold, the powder flask. The syringe had some age to it. The ivory crucifix which doubles as a wooden stake, were period, too.”

But there were suspicions. The items seemed to mix vampire legends and traditions. Silver bullets? That’s for werewolves, isn’t it?

“It seemed to reflect more of the literary and popular culture tradition of vampire lore, not the traditional folk legends of vampirism,” he said.

As it turns out, the kit is likely fake, although belief in vampires and how to dispatch the “undead” was real in Europe.

At the time the museum acquired the kit, similar kits suddenly arrived on the auction market, Amsler said. Each kit contained slightly different objects, but always noted Prof. Blomberg and the gunmaker Nicholas Plomdeur.

“What occurred to us is that someone was very likely assembling material and putting it in a different context. You know, finding a case that had been designed for a dueling set or a pistol case or something like that and recontextualizing the objects and presenting them as a vampire killing kit,” Amsler said.

If the museum’s aware of their kit’s fakeness, why do they still display it? Amsler elaborates in the same article:

The Mercer decided to display the kit full time because its curiosity value mesmerizes. The museum incorporates it into its annual Halloween “Mercer by Moonlight” tours to explain how the living could believe in the “undead.”

“The essence of vampirism is that somehow a dead individual is able to reach from the grave to suck the life from the living. But it really was a way for pre-modern cultures to explain the mystery of epidemic disease,” Amsler said.

If it’s starting to sound like museum’s are in on a “gag,” you’re probably not far off the mark. Let’s jump back to the Royal Armouries Museum, Leeds, which pops up in David Barnett’s Postcards from the Hinterland blog post, “For Sale: Vampire Hunter’s Kit. One Careful Owner…” (August 24, 2012):

But after purchasing the kit, the Royal Armouries revealed that although the individual parts were most likely Victorian era, the kit “was probably compiled in the late 20th Century following the success of the Hammer Horror Movies and inspired by Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula”.

The Royal Armouries’ Curator of Firearms, Jonathan Ferguson, told me, “The contents are 19th Century – although one antique box expert says the box may be c1920. Research shows that kits of this nature were assembled in the second half of the 20th century. We will carrying out tests to confirm the facts.

“So, it’s Victorian in the sense that it’s made of Victorian components and intended to represent something from the mid-C19th. It’s 20th century in terms of when it was actually put together, inspired by post-Dracula vampire fiction. This was well known by us, and others, well before the auction came up and we were open with the auctioneers.”

Ferguson maintains the kit’s relatively recent vintage, but also uses it as an “educational” tool the same way the Mercer Museum does. On October 25, 2013, Leeds-List promoted an October 30, 2013 talk by Ferguson called “How to Kill a Vampire,” mentioning:

The kit has been on display since last year [2012] in the Firearms Curiosa area of the Royal Armouries. Although it’s an interesting exhibit, Jonathan Ferguson himself believes that it isn’t genuine – seeing them as props for a film that doesn’t exist – but still, it’s a testament to how prevalent vampires and their mythology are at this point in popular culture.

But famous pawnbroker, Rick Harrison, clearly doesn’t share the cultural values Amsler and Ferguson invest in the kits. In Pawn Stars episode, “Rick or Treat” (S4E52; October 24, 2011), Edmondo, an antique company owner, stops by Harrison’s World Famous Gold & Silver Pawn Shop, Las Vegas, looking to shill an “original 19th century vampire killing kit” for US$9,000—a figure based on “research.” (1:20–4:08).

[su_dailymotion url=”http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xlycc0_pawn-stars-rick-or-treat-s04-e52_shortfilms” quality=”240″]

Instead of handing over cash, Harrison eviscerates Edmondo’s asking price with two deft strokes: his familiarity with vampire lore—recognising Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) has influenced the kit’s components, thereby gauging a later-than-assumed date—then focuses on the kit’s inclusion of an “obsolete” 1830s firearm. “In the 1890s, they didn’t even make parts for this any more. They had really cheap revolvers.”

“My conclusion of the kit…is much later than 1900,” Harrison says, adding, “Someone did an amazing job of putting this thing together, but the devil’s in the details, there’s a couple of things that tell me this is fake.” The only “value” Harrison sees in the kit is its firearm. If only other kits were given the same scrutiny.

We’re now left with an obvious question: if these kits are fake, who’s making them? If we’re dealing with a “copycat” trade, can we pinpoint someone responsible for instigating the trade? Do we have any suspects? Has anyone stepped forward to claim forgery? Funny you say that…

#3. Someone’s Confessed to Faking the Original Kits

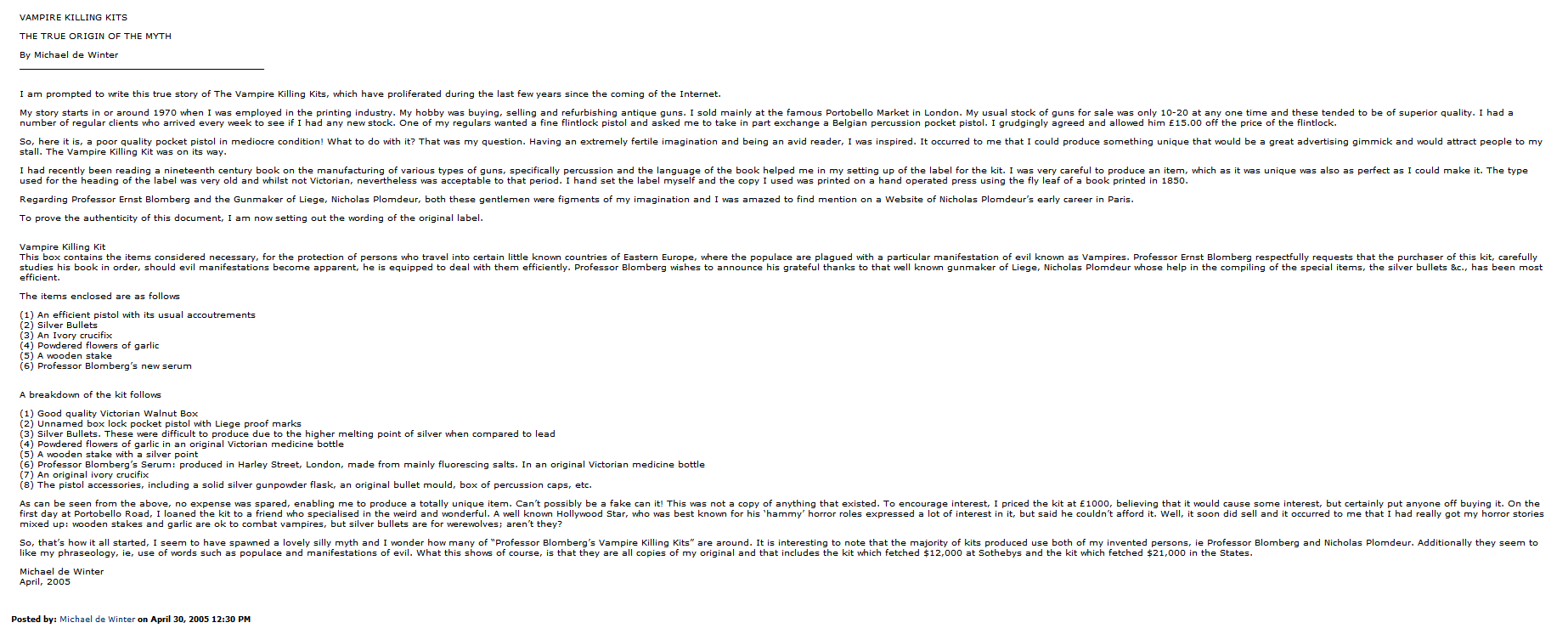

On January 10, 2005, Michael de Winter from Torquay, U.K., burst onto SurvivalArts.com message board thread, “Rare Mid to Late 19th Vampire Killing Kit,” with a bold announcement:

Hi there! You should know that all the quotes on your site are a load of codswallop. The reason is this: The whole VAMPIRE KILLING KIT myth is purely the result of my very fertile imagination and I produced “The Original” in 1972. Nicolas Plomdeur the Gunsmith in Liege and Professor Ernst Blomberg are not and have never been real people. I still have an original copy of the label from the box and am astounded to learn how my joke has caused so much interest and “FAKERY”

After offering to share his story in a Word document via email, members successfully goaded him into posting the story on the board, which he published on April 30, 2005 as “Vampire Killing Kits: The True Origin of the Myth”:

My story starts in or around 1970 when I was employed in the printing industry. My hobby was buying, selling and refurbishing antique guns. I sold mainly at the famous Portobello Market in London. My usual stock of guns for sale was only 10-20 at any one time and these tended to be of superior quality. I had a number of regular clients who arrived every week to see if I had any new stock. One of my regulars wanted a fine flintlock pistol and asked me to take in part exchange a Belgian percussion pocket pistol. I grudgingly agreed and allowed him £15.00 off the price of the flintlock.

So, here it is, a poor quality pocket pistol in mediocre condition! What to do with it? That was my question. Having an extremely fertile imagination and being an avid reader, I was inspired. It occurred to me that I could produce something unique that would be a great advertising gimmick and would attract people to my stall. The Vampire Killing Kit was on its way.

De Winter’s story is compelling, but admittedly not conclusive. There’s no photographic evidence accompanying his posts, and other forum members cast doubt on his claim as a vampire killing kit originator, including someone named Ed: “I have a Vampire & Werewolf Killing Kit that i picked up at an auction in 1969. Now that is 3 years befor 1972. The boxed set was very old at the time i [sic] got it.” (December 6, 2006)

Unfortunately, Ed made no further contributions to the thread—which only exists on Internet Archive: Wayback Machine, because SurvivalArts.com is defunct; its URL available for purchase. I tried contacting de Winter on October 30, 2014, via an email address he posted on the thread, but my message bounced back, indicating his email address is defunct, too.

You can read a thorough breakdown of de Winter’s claims on the Spooky Land website’s “Regarding Ernst Blomberg” page—which argues for and against de Winter’s claim. For instance, despite de Winter’s insistence he invented Ernst Blomberg and Nicolas Plomdeur, there actually was a 19th century professor and Belgian gunmaker of those names, respectively. De Winter countered on the SurvivalArts.com thread with:

At the end of the day, I did think up the name Nicolas Plomdeur, so the fact that there was someone with that name is truly pure coincidence. By the way, Alexandre Dumas and Daphne du Maurier both thought up “DE WINTER” and as you know, that’s my name. (November 18, 2005)

And

Hi there. NO, I’m not lying! The truth is on this site as The TRUE Story. I still have not seen ANY evidence Re Professor Ernst Blombergs’ existence before c1972. I agree however that there is evidence available indicating the gunsmith Nicolas Plomdeur did exist, but have stated elsewhere that this is just coincidence.

I stand by my story and await without trepidation for anyone to prove otherwise. (February 18, 2006)

De Winter’s challenge to for anyone to successfully confirm a historical link between Blomberg’s and any vampire kits—both on and off the thread—remains standing. His claims to fakery—more accurately, fakes springing from his original fake—are given further credence by the artificially-aged and incorrectly-attributed writings subsequent kits have bestowed on Blomberg, something I discussed in my Vampirologist blog post, “Dismantling Vampire Kits” (October 3, 2011).

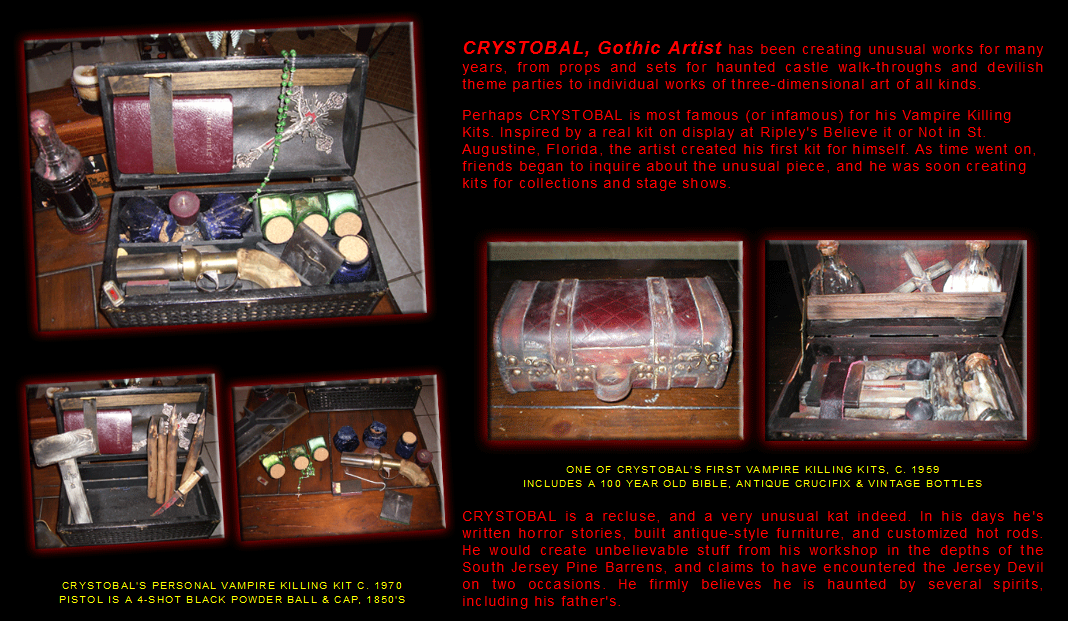

But de Winter’s not the only one claiming the “Father of All ‘Antique’ Vampire Killing Kits” title. Christopher Pinto offers another contender in his StarDust Mysteries by Christopher Pinto blog post, “Vampire Killing Kit for Sale on eBay” (September 10, 2011): a “Gothic Artist” named “CRYSTOBAL”:

CRYSTOBAL is the artist credited with starting the repro [sic] Vampire Killing Kit crazy [sic] in the late 1990s. He’s been building these kits for stage, screen and private collectors since the 1950s, and without doubt is the premier builder of these historic pieces. Many have tried to imitate his work, in fact some even have the audacity to claim to have been the first to create this style of kit, but none have been able to come even close to his unique and original style of 19th century, primitive Vampire Slayer Kits.

If you follow the link in Pinto’s blog post, you’re taken to the “CRYSTOBAL’s Vampire Killing Kits & Other Horrific Works of Art” page, which is also part of Pinto’s Star Dust Mysteries website—meaning Pinto was actually referring to himself (“CRYSTOBAL”) in third person. Here’s how Pinto describes Crystobal’s work:

Perhaps CRYSTOBAL is most famous (or infamous) for his Vampire Killing Kits. Inspired by a real kit on display at Ripley’s Believe it or Not in St. Augustine, Florida, the artist created his first kit for himself. As time went on, friends began to inquire about the unusual piece, and he was soon creating kits for collections and stage shows.

Crystobal’s page features two images, captioned “ONE OF CRYSTOBAL’S FIRST VAMPIRE KILLING KITS, C. 1959” and “CRYSTOBAL’S PERSONAL VAMPIRE KILLING KIT C. 1970.” Both years compellingly pre-date de Winter’s claim—but they’re easily quashed when we refer back to Edward Meyer’s statement about Ripley’s vampire killing kits: “No, we have nothing any earlier than 1990 mentioning their existence.”

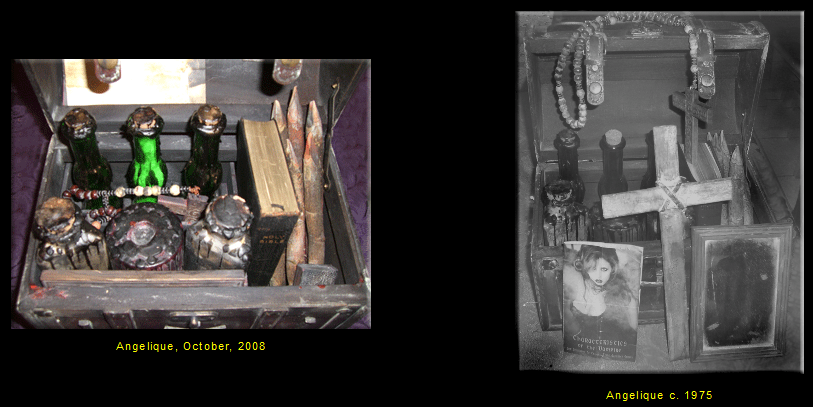

I’ve reproduced a screencap from the page, because if you click on the “ONE OF CRYSTOBAL’S FIRST VAMPIRE KILLING KITS, C. 1959” photo to enlarge it, you’re re-routed to a page for Crystobal’s kit, “Angelique” The page says, “Below left is a picture of the same kit taken recently [2008]; below right is a photo of the same Vampire Killing Kit Crystobal took around 1975,” but it’s obviously just a modern photo with a black and white filter.

The dates Pinto/Crystobal gives for his vampire killing kits are clearly false, too. His “How It All Started” page details the formation of his company, Stardust Productions:

I actually lived in the Stardust Motel [Atlantic City] when i [sic] was a little kid. My parents ran the motel that sat on the Black Horse Pike on the way into Atlantic City; We lived in the house/office built into the front of it. So I took the name of the motel my mother and father ran in the early 70’s (and of course from the song), I set out on an experiment to see if i [sic] could write, produce, direct and star in my own dinner theater show. Stardust Productions was born.

If Pinto was a “little kid” during the 1970s, he obviously wasn’t producing vampire killing kits from 1959 onwards. If you needed any more signposts to Pinto’s elaborate fakery, he’s also written a book called How to Kill Vampires (Because They Are Unnatural Jerks) (2013).

It’s subtitled, “A Guide to Slaying the Beast, by CRYSTOBAL, Gothic Artist and Vampire Hunter; Original Creator of the Modern Primitive Vampire Killing Kit.” If you’ve got any doubts left about Crystobal’s identity, clicking on the book’s “Look Inside” feature will reveal the book’s “Set in readable text by Christopher Pinto, Master Mystery Writer” and copyrighted to “Christopher Pinto/StarDust Mysteries Publishing.”

As it stands, the earliest contemporary references we have to vampire killing kits—as opposed to latter-day testimony, hearsay and elaborate frauds—post-date de Winter/Pinto’s accounts. After all, the Mercer Museum acquired its “Blomberg” kit in 1989 and BS Historian says Phil Spangenberger’s Guns & Ammo article, “Vampire-Killing Kit” (October 1989) is “The first printed reference to the existence of the kits” in their blog post, “Vampire Killing Kits 2” (September 1, 2010).

But I’ve come across something earlier. Harry L. Rinker’s Morning Call (Allentown, Pa.) article, “Wilkie Bust Light Can’t Hold a Candle to Roosevelt Model” (December 13, 1992) discussed reader feedback on vampire killing kit commentary he’d been making in his column. Two particular mentions stand out as probable precursors to Spangenberger’s 1989 article:

Bonnie Keyser of West Chester reports that she and her husband saw a Vampire Killing Kit sell for several thousand dollars at the January 1986 Manhattan Pier Show. She noted in her letter that Bram Stoker’s Dracula novel was first published in 1897, making a Vampire Killing Kit from the mid-19th century somewhat suspicious. Her feeling at the time was that the kit dated from the 1930s.

And:

Patrick Kelly of St. Paul, Minnesota, sent me a photocopy of a portion of the Houses of Swords and Militaria’s (Independence, Missouri) 1986 Catalog 22 in which a Vampire Killing Kit was offered for sale at $850.

Though we need to rely on more than just Bonnie Keyser’s “feeling” to verify her 1930s estimate, we’re still left with two independent sources—one hearsay, one photocopy—pinpointing “antique” vampire killing kits to 1986. Those kits set benchmarks in other ways, too: their high sums set the precedent for what’s become a thriving trade—with major consequences…

#2. Buying Them Encourages More to Be Made, Sold and Displayed

I first delved into kits with my Diary of an Amateur Vampirologist blog post, “The Scoop on Vampire Hunting Kits” (July 21, 2010). The next day, I’d already dubbed their spread “The Blomberg Effect,” referring to “The demand for these derivatives, and the subsequent market it’s spun off”.

If de Winter’s right and he crafted the first kit, we’re dealing with a thriving trade for fake antiques. Think about that a moment. Isn’t the point of trading antiques their age? That they’re supposed to be the age they’re advertised being? Isn’t their value determined by historical significance or scarcity? When it comes to “antique” vampire killing kits, people are spending thousands of dollars—on what?

After Sterling Associates Antiques told me they couldn’t verify the age of their “19th Century European” vampire killing kits and admitted they weren’t vampire killing kit experts, I asked, “if you admit you’re not experts on the vintage of these kits, and your research is limited on them, how are you justifying selling them for $4,000-$5,000?” They said, “Our conservative estimates are based on previous auction results of similar items.”

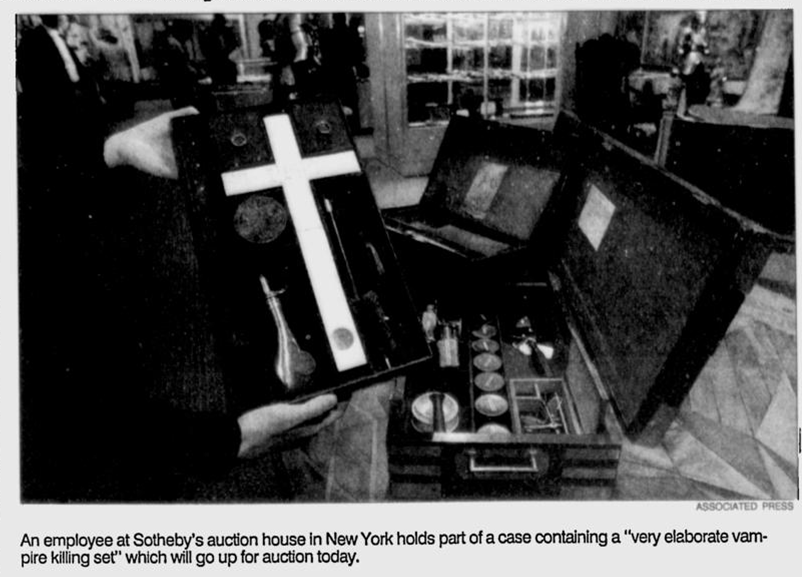

The precedent set by the sales of “antique” vampire killing kits from the 1980s onward has created a demand—a demand for “historical” items nobody’s properly authenticated. That’s insane. And it gets crazier still. Rick Hampson covered the advertised sale of a “A Very Elaborate Vampire Killing Set,” a Blomberg kit, no less, in his Associated Press article, “Lot 394: Vampire Killing Made Easy” (January 9, 1994):

The kit probably was assembled in 20th century America, not 19th century Europe; the cross-pistol looks like it’s from the 1830s, but was really made within the last 15 years; and if there was ever a ”Professor Ernst Blomberg,” supposedly the name of the kit’s creator, he has not gone down in the annals of vampire fighting.

”I’m afraid it’s only a pastiche, a romantic curiosity,” said Nicholas McCullough, a Sotheby’s consultant. ”There was never a vampire killing kit.”

”The case itself is mid-19th century, probably English, of no particular rarity,” added McCullough. ”But presented as a vampire killing kit, it opens up whole new vistas. Everyone’s intrigued by it, from interior decorators to jokesters.”

A vampire, of course, recoils from garlic, the Bible and the cross; he is vulnerable to silver bullets and, if asleep in his coffin, a stake.

What about a mirror? ”It may be missing,” said McCullough, whose knowledge of vampires comes mostly from horror movies. ”I’m looking for vampire prints.”

McCullough said he didn’t know who assembled the kit, but had an idea why: ”To make money.”

Sotheby’s says it expects the kit to sell for $3,000 to $4,000, with the proceeds going to the anonymous American owner.

Would you still buy the kit after hearing that? Doubt it! So, how much did it sell for? It turns out, an anonymous phone bidder bought the kit well above its asking price according to a January 12, 1994 news brief hosted on philly.com called “Vampire Kit Fetches $12,000.”

No wonder an entire industry’s sprung up from their sale and manufacture, but the implications are dire. For instance, let’s say that somewhere out there, genuine 19th century vampire killing kits exist. How will they be recognised if auction houses, antique dealers—and even buyers—care so little about authentication? If unverified kits have been in circulation for nearly three decades, what about other antiquities?

Is that antique Ming vase you bought at an auction legit? Was it “authenticated” with little more than a cursory glance? Think about it. Once buyer-dealer trust is compromised to the extent it clearly has in the “19th century” vampire killing kit trade, we must ask the antique trade industry some hard questions.

On a lighter note, there are much more viable options available to you without making bids on “antique” vampire killing kits and warping the antiques trade into something Han van Meegeren (1889–1947) would be proud of. And best of all, you don’t have to take out a second mortgage…

#1. You Can Make or Buy Your Own Cheaper Kits

If you’re really desperate for an “antique” vampire killing kit, consider three options: 1) scour 19th century literature and antique houses the world over for the mention or presence of genuine antique vampire killing kits, 2) make your own or 3) buy one from a seller who openly admits to manufacturing them.

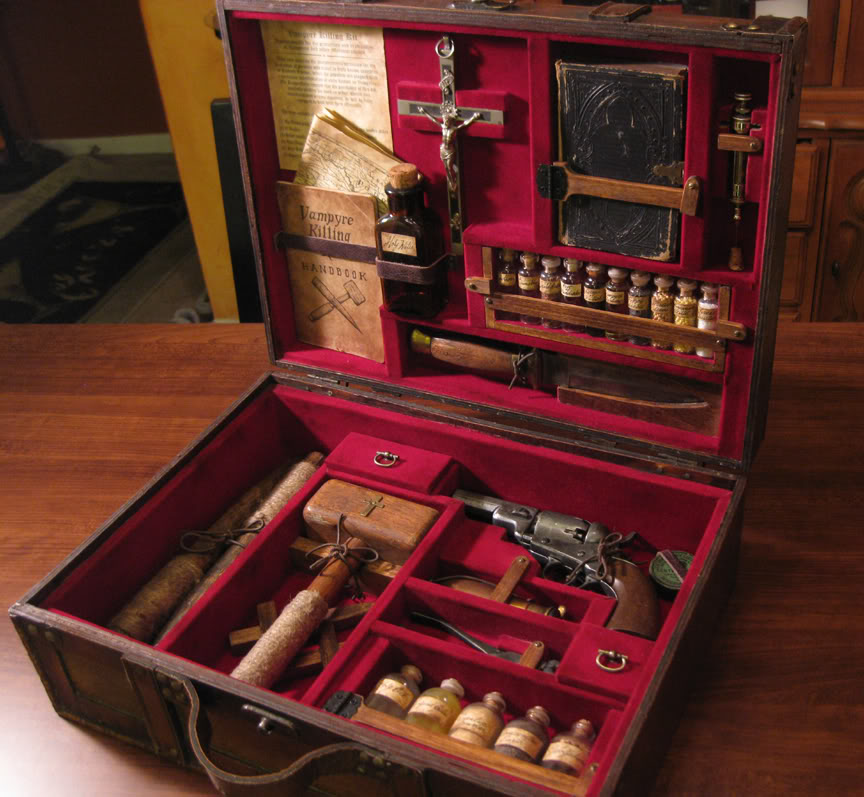

For the sake of this entry, we’re only going to deal with the second two options. To cover the bare basics, read Christi Alridge’s eHow tutorial, “How to Make a Vampire Killing Kit” (August 14, 2014). It also turns out Auction Kings “Vampire Hunting Kit” episode had some value after all: inspiring an RPF forum member named “Darth Saber” to use their initiative:

My wife, who’s a vampire fan, looks at me and says “That’s one of the coolest things Ive ever seen…You should make one.”…Needless to say , my mind was already working out all the materials I would need to make one.

So, I went ahead and picked up one of those home decor trunk/suitcases. THey usually sell for about 25-30$ at Michaels or other craft stores. Usually these kits are made from 19th century lap desks, but I wanted something with a handle and some vintage accents on the outside (Lap desks dont usually come with handles and the ones with vintage designs usually run $200-$400)

And so on. “The Vampire Killing Kit or “The accoutrements for the eradication of vampires”” thread he kicked off on March 12, 2011 documents his efforts. Here’s how it looked by March 30, 2011:

The final product was completed by April 15, 2011. Note the additional items and the way Saber’s kit has been artificially aged. Doesn’t look much different from the “real deal,” eh?

On April 4, 2011, he mentioned the kit’s assembly had cost him “about $350…However, after figuring out some things by making this kit, I could probably cut down the price to about half if I made another one.” On the other end of the scale, Megan recounts making one for US$26 in her Polish the Stars blog post, “Vampire Killing Kit” (October 15, 2011).

If making one sounds like too much effort, you can buy one, pre-made. A whole bunch are available from Phineas J Legheart Vampire Killing Kits. Prices range between US$50 for the small “Vampire Tears” model and US$295 for their largest kit, “The Bastille.” If you’ve got more cash to spare, you can’t go past The Specimens of Alex CF.

His artwork Lovecraftian designs will blow your mind. Check out his “Vampiric Anatomical Biological Research Case,” for instance. The kits—and other “specimens,” read: artworks—are part of a compelling narrative arc he’s created and chronicled on his “Encyclopædia Obscura” page, which recasts vampires as an evolutionary strain called Homo vampyrus. Brilliant stuff.

Christopher “Crystobal” Pinto also has his own vampire killing kits website called, Vampire Killing Kits by Christobal. Despite the nonsensical statements on the site’s “Who is CRYSTOBAL, GOTHIC ARTIST?” page (“CRYSTOBAL is one, CRYSTOBAL is many. He is 80+ years (four lifetimes) of experience in one spirit”), he at least has the integrity to admit his kits are fake:

Below is basic chart of the elements that CRYSTOBAL has in his kits, vs. the original kits. Also, you should not that the original “real” vampire killing kits were small…usually around 14″x 7″x3″ or less, were made from wooden boxes made to sit flat on a table (not the best for travel), and almost all were supposedly built by a “Professor Blomberg”. CRYSTOBAL never tries to imitate these original kits, or to use Blomberg as a reference.

Even if he’s fallen for the “19th century” claims, too:

As you can see there are extensive differences between the CRYSTOBAL style kit, and the original 19th century kits. It is CRYSTOBAL’s style that has become the trend today, as he had the foresight to anticipate that today’s market would require more than just a few drops of holy water, or a single stake. By taking cues from books, movies and TV shows (such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer), CRYSTOBAL was able to create a new, more extensive vampire hunter’s kit, while keeping the antique-style charm and artistry of a hand-made, 19th century kit that would have been useful in an actual vampire attack.

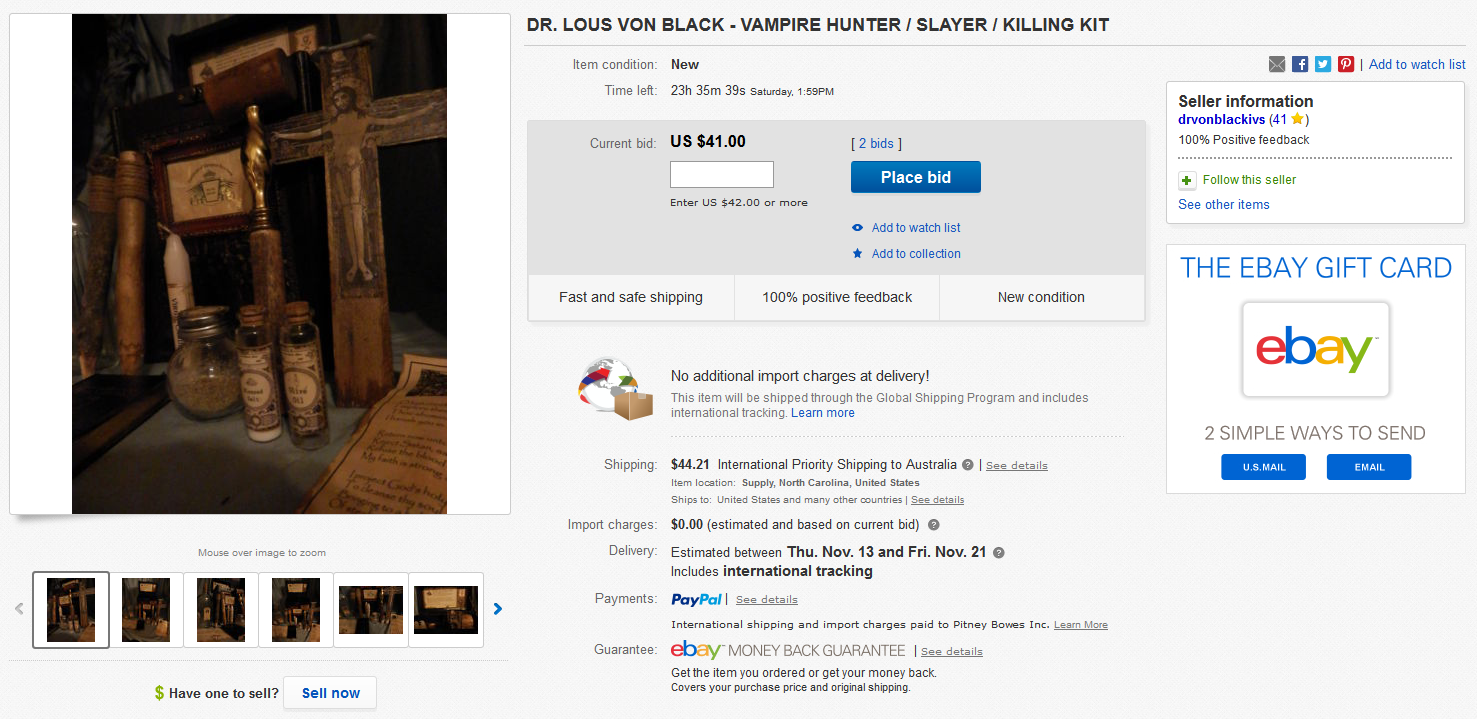

You can even try eBay. Search for vampire killing kit, vampire hunter kit, vampire slayer kit, vampire kit, vampire hunting kit—hell, even buffy vampire kit—and you’ll find many examples every bit as “genuine” as the ones sold through auction houses, for a fraction of the price.

If you’re after something particularly sleazy, try Di Stefano Productions’ 12” x 15” wall-hanging wood and glass Vampire Hunter’s Kit (“Roman Catholic Approved”) for US$85. You could pair it with their Vampire Stakes & Cross Wall Hanging Set (US$39.95), Vampire Killing Stakes (US$24.95)—or if you’re feeling particularly gruesome—their Female Vampire Corpse, which comes with “Removable wooden stake” (US$600).

Contact them before purchasing anything, though: the site hasn’t been updated since 2008. Incidentally, I’m not recommending any of these things so you can go forth and start making thousands from auction houses, antique dealers—or even pawnbrokers. No, I’m telling you this because there’s clearly a significant demand—and that demand must be satisfied in a safe, productive way.

It’s like teaching contraception to teenagers: it’s not that you want them to sleep around, but it beats letting them carry on in ignorance, catching STIs, getting knocked up, all that grisly stuff. When it comes to “19th century vampire killing kits,” it’s private buyers, auction houses, museums, pawnbrokers, antique dealers and the antiquity trade itself getting fucked instead.

This article was inspired by the “Vampire Lore and Legends” Facebook thread James Lyon kicked off by sharing the Sophie Jane Evans Daily Mail article mentioned in the first entry. Now for some “further reading” recommendations.

Joe Nickell conducted his own investigation into vampire killing kits and published his findings in Tracking the Man-Beasts: Sasquatch, Vampires, Zombies, and More (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2011), pp. 125–8. You can read an excellent Buffalo Story Project profile on Nickell called, “Hunting Monsters, Chasing Ghosts: The Marvelous Life of Detective Joe Nickell” (May 24, 2012).

Jonathan Ferguson also wrote an excellent article called “To Kill a Vampire” for Fortean Times, no. 288 (2012). Contact the magazine to see if you can score a copy. The issue has other vampire goodies, too—its front cover also features Darth Saber’s kit!

In the meantime, read D.A. Lascelles’ interview with Ferguson here. If you’d like to see Ferguson in person, he will be discussing vampire killing kits at the British Library on November 9. For further details, click here.

If you’re still in the mood to make your own kit, Shawn & Lynne Mitchell’s How to Haunt Your House: Book 3 (Penascola, FL: Rabbit Hole Productions, 2011) features a guide to making an “Ultimate Vampire Hunting Kit.” Google Books preview here.

Anthony I read the entire article, which is quite lengthy lol and I have to say this is one of the best articles you have written to date! Thoroughly enjoyed this and now we can call you a ‘vampire killing kit’ expert. 🙂 I loved this bit, “It’s like teaching contraception to teenagers: it’s not that you want them to sleep around, but it beats letting them carry on in ignorance, catching STIs, getting knocked up, all that grisly stuff. When it comes to “19th century vampire killing kits,” it’s private buyers, auction houses, museums, pawnbrokers, antique dealers and the antiquity trade itself getting fucked instead.” Amazing job and a lovely treat for Halloween!

I took a gamble with that ending, Erin! I only had minutes to spare before Halloween was over! Call it last minute inspiration.

And thank you kindly. 🙂

Thanks for sending me to this earlier article. I’d been meaning to take a look. Back in college, I took a class entitled “The Paranormal and the Scientific Method” where we examined numerous cases of intellectual fraud and this is clearly one of them. People are manufacturing these kits and passing them off as “antique” in order to bilk poor suckers from their money. I also very much appreciate the final point. I spend some time in Steampunk circles and it occurred to me that there ought to be a market for nice kits sold for what they are — decorative items that show one’s fondness for vampires which you could display in the home. I’m pleased to see there are some people doing exactly that, and charging fair prices for their work rather than passing them off as antiques and selling them for exorbitant prices.

You’re welcome, David. That class sounds fascinating! And I agree with you, they’re being manufactured in order to “bilk”…but what disturbs me most is who’s selling and who’s buying.

All consumers should employ “caveat emptor,” but you’re less likely to do that if an auction house or antique firm says they’re genuine. It’s only with further probing that their superficial investigation comes to light.

In this very article, we have a marked contrast between how they’re handled on two different reality shows.

I think the “steampunk” angle is a big part of it. And that’s fine…if the kits were accompanied by disclaimers. They’re not. Instead, we’re dealing with a flood of fakes which are legitimised through unquestioning media coverage and the high prices they sell for, which sets the benchmark for more. I’m just glad people are waking up to what’s going on here.

One thing you’ve not yet mentioned is that like the Salem witch scare, the US went through it’s own period of rampant vampire fear. It was confined to rural areas of North Carolina and parts of the east coast, but it was no less frightening in some ways. One particular incident stands out above others. In that case, a young girl died of “consumption”, and she was buried by her grieving family. Within a few weeks later, others in her family started to show signs of the same wasting condition, which led some in the village to fear that the rumored vampires had infected their village in the form of the recently buried girl. As I recall, the village elders took it upon themselves to exhume the body, and that’s when they find that, outside of smell and some other small unpleasant traits, the body appeared to still have some features of life about it still. A hasty decision was made to consult the local priest who declared on the spot that it would be safest to burn the poor girl’s remains. But, this is where he took it to a grisly extreme. He decided that to save the remaining family members from the taint of vampirism, the father must mix the dead girl’s ashes with liquid and drink it, as a sort of medicine. Sadly, despite their efforts, persons who exhibited symptoms went on to perish despite the cleric’s efforts.

I too, have spent many years studying the killing kits, and most specifically, each and every item in the “Blomberg” kits in particular. One thing that seems to be reliable is that every tincture, powder, oil, and so forth is a form of purification. Silver is said to be repugnant to vampires because Judas sold out Jesus to the Romans for 30 pieces of silver, thus silver is forever denied to the hands of evil. In most of the known examples of “vampire” graves, wooden stakes are not used. In Europe and areas furher east, those said to be vampires were buried staked to the ground with iron stakes, and sometimes a large rock jammed into the jaws. It is notable that iron is a historical way to “seal” or “bind” evil. Thus, within the grave, the vampire was in essence, pinned to the ground by one or more stakes through his or her body. Sometimes the heart was pierced, but not always. Other ways to stop them was to behead them and place the head below the knees. This meant that the pinned body could not reach its head and could not “heal” and free itself in some way.

In short, without going into further elements of my research, I am of the considered opinion that some kits were probably constructed during that period when Americans feared the supernatural on the east coast. Later, when such things were downplayed as ridiculous and even laughable, the few actual kits were left in attics or closets and long forgotten, possibly purposely, to prevent any further embarrassment for having been involved. So who did them? Well, that’s where the study of the contents gets interesting. As I said, most all the medicines were purifiers of some kind, and all of them easily obtainable by physicians or a druggist looking for a little extra cash to be gotten by playing on the fears of some of the locals. Cobbled together one at a time, then sold to either frightened locals or better, immigrants who brought native fears with them, the seller, whoever it was, could probably make a “killing” just like they are trying to do now, based on the legends, the excitement, and the “authentically worn” appearance of the items. In the same period as the snake oil scams, such a kit might well bring in a lot of cash in outlying areas where there are few newspapers. All you’d need was a terrifyingly good spiel of stories and a carefully chosen village of rubes and you’d be all set, while your outlay would be a collection of second-hand oddments and inexpensive “medicines”. And the prettier the box it all comes in, the more convincing it is.

I still have a very long way to go in my research, but I find it entirely believable that some kits could be genuinely antique. Will it ever be proven one way or the other? I don’t have that answer, yet, but I’ll keep digging. For instance, I’d REALLY like to find out what’s in the tube labelled “vampirism”. I’ve solved all but that one, and so far, Ripley’s museum has not answered my queries. I’d even pay to have it professionally analyzed. Other than that, there is little of mystery in the construction, and most of those making the kits today make obvious errors when they base their kit re-creations on the book DRACULA, or worse, the more modern vampire “lore”.

Your article is an interesting one, but I would hesitate to dismiss authenticity too eagerly. Even snake oil bottles prove that some people believed that some whiskey or brandy with some miscellaneous herbs and such tossed in could cure most all ailments known to mankind, so I find it entirely feasible that one or even more kits could convince a rural village that they too, could be victims to a vampire. That said, I also thoroughly believe that the public should be warned about the utter lack of any verification and to spend their money wisely when it comes to any article purporting to protect people from supernatural beings. There is a veritable flood of items made for the mass market coming out of Indonesia these days, and they too, hope to cash in on the vampire fever with various amulets, statues, and tokens.

Hi InuNoTaisho,

Thank you for your comments. I’ll now take the opportunity to address them.

The “rampant fear” you speak of (primarily in New England) concerned a distinct version of the vampire myth; primarily a way of dealing with tuberculosis sufferers. For more, see Michael E. Bell’s excellent book “Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England’s Vampires” (2001; 2011). The story you told seems to be a variant on the Mercy Brown case. See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercy_Brown_vampire_incident

The kits in question, however and as noted, share more in common with the European type, specifically, post-Dracula fictional representations. Indeed, your commentary on the vampire’s aversion to silver is derived from the movie, “Dracula 2000” (2000).

Those are giveaways to their fakeness. Wooden stakes were actually much more common: the “vampire” burials you describe are more like deviant burials; “vampire” is often amended to them as a catch-all for burials of those types, but note that no explicit connections are made to the corpse’s supposed vampirism. Also consider this: wooden stakes would have been much more common because the material was more plentiful and cheaper to the villages were vampire attacks were most often reported.

There is zero evidence these kits — any of these kits — were manufactured during the 19th century in the US or elsewhere, which was the whole crux of the article. There’s certainly a “snake oil” element involved, but that’s what happens when these things are palmed off as “antiques” without any serious efforts to verify their historicity in the first place; Edward Meyer, responsible for the world’s largest collection of these kits, says there is no reliable evidence indicating they were manufactured prior the 20th century.

Believability or plausibility, if you prefer, is no substitute for actual evidence. As it stands, there is zero. But don’t let that discourage you from your search for an authentic kit. If anything, I wish you all the best on it. And I would happily give coverage to a genuine kit here.

Excellent article! Well researched and well presented. It’s important that people realize there are unscrupulous sellers out there who are trying to pass off reproductions as originals.

However your assumption that CRYSTOBAL and I are one and the same is not entirely true. I will let the cat out of the bag: CRYSTOBAL is more than one artist (CRYSTOBAL is one, CRYSTOBAL is many). He/they have been creating theater props, etc. since the 1950s. The first CRYSTOBAL kit was actually done in the 1950s, mostly inspired by Hammer films. You’ll also note that CRYSTOBAL kits are very different from any of the kits featured at Ripleys, and it is this style of hand-made kit that CRYSTOBAL (all of them) take credit for originally designing.

You’ll also note that at no time does the artist, or I, infer that these kits are antique, genuine or original to any specific era. They are not fake – they are works of art that enjoyed by the dozens of people who have bought these replica kits.

You’ll also take note that CRYSTOBAL is representative of a genre of pure fiction. There are of course no real vampires, so there are, of course, no real vampire hunters, or “real” vampire kits. It is all pure fantasy, and as such, nothing on the subject should be taken as fact or history.

Again, well done article.

-Christopher Pinto, author of the Detective Riggins murder mystery series, and co-writer of “How to Kill Vampires because the are unnatural jerks” (But not CRYSTOBAL)

Hi Christopher,

Thanks for writing in! I must confess I’m not completely sold on the “The first CRYSTOBAL kit was actually done in the 1950s, mostly inspired by Hammer films” bit because the first Hammer vampire film was 1958’s “Dracula” (US: “Horror of Dracula”) which still puts it outside your timeframe. However, if you have any evidence to the contrary, I’m more than willing to hear it out/view it.

I appreciate that you don’t promote them as genuine kits, that they are more like representations of the ones palmed off as genuine. I certainly agree with you on the fantasy points though!

Regards,

Anthony

Very good posting and I was intrigued by your conclusions.

I’ve read some of the other research and previously noted the various ‘vampire killing kits’. Although there might remain an outside possibility of the genuine article in existence, the facts do appear to throw a great deal of doubt toward the authenticity of most, or an alleged historical basis for their existence. The main components do have a large degree of antique quality in common, while little else can be ascertained beyond some assuredly strong hints of clever impostures. I, too, followed your link and enjoyed this further in depth analysis. Keep up the good work you’ve been deeply involved with for quite a few years!

Regards,

~ Al

Hi Al,

I’m certainly open to the possibility of a genuine antique vampire killing kit; but all the evidence points to no such thing, being mindful that we’re also talking about museum displays and auctions sales here, too.

The antique quality in question involves both including genuine antiques (the firearms) with artificially aged items. Don’t get me wrong, I have no problem with people making pseudo-antique kits, hence #1 on the list, but to present them as genuine antiques is simply fraudulent. I can’t stand for that, no.

Thanks for your kind words!

Who the fuck cards if they’re fake or eeal? What a fucking stupid and useless article. What matters is how cool they look.

By fuck, you internet “journalists” are such hacks,

Hi Pete,

Firstly, before posting your comments, consider using a spellcheck. Second, who cares if they’re real or fake? I’d think the people buying them would, or people visiting the museums they’re displayed in. So, yeah, there’s more to it than just “how cool” they look.

Considering you couldn’t fault any of the content, I’m boggled at your “hack” reference. I wasn’t aware that accurately reporting on something counted as “hackery,” but I guess not all of us can aspire to the lofty journalistics heights of, uh…the Venture Bros.

Hi Anthony,

I ended up finding your very interesting article after seeing an “Antique Vampire Slaying Kit” featured in an article in today’s WSJ.

It is supposedly for sale by M.S. Rau Antiques and contains 12 items for a price of $14,850!

I was particularly amused by the 850 part, wonder how they came up with that price?

I found your article because I thought I remembered an episode of Pawn Stars where one came into the store. This kit advertised in the paper today also has a percussion type pistol despite claims of it being “vintage late 1800s”.

Interesting.

Anyway this was a good read, thanks.

Phil

Hi Phil,

Thanks for the wonderful feedback! Is this the WSJ article? http://graphics.wsj.com/image-grid/listfall-2016/3064/12-components-of-a-19th-century-vampire-killing-kit

The Pawn Stars episode you might be remembering is “Rick or Treat,” which is covered in this very article! (Under entry #4)

Such a well-researched and entertaining article on such a hilarious idea!! As if any British or North-American gentleman planning to travel to Eastern Europe ever would think of ordering such a kit, hahaha! First of all, as a good Christian, he would never adhere to such superstitions about vampires — provided, he had ever heard of them at all! Just read Jonathan Harker’s Journal in “Dracula” to understand that no western traveller in his right mind would ever consider to take precautions against “vampires,” that do not even exist in Romanian folklore (the supersition originated from Serbia, as we know today). Secondly, if he needed proper anti-vampire equipment, he would be done in a minute: the gun and the Bible were already on his night desk, crucifixes were hanging on the walls of his house. A bottle of Holy Water could be procured at any Catholic Church at no cost.. for garlic, he would ask his kitchen maid, and for some pointed sticks, his gardener or the local carpenter — ready is the Anti-Vampire Tool Kit 🙂 That authentic-looking 19th-century items are difficult to get by today should not let us forget that in the 19th century, they were literally everywhere 🙂 No need to order a “Blomberg Toolkit” in Boston…. just grab your daily seven things and throw them into your carpet bag… ready is the amateur Vampire Hunter. People who do not realize this should not be allowed to hold 5,000 US $ or more…. The only buyer for whom the “Vampire Killer Kit” pays off is the local museum: to generate extra revenues from dumb-headed visitors. Even if the provenance is questionable, some excuse will be found to exhibit the item all the same, and collect the entrance fees. Mundus decipi vult… Better buy an early edition of “Dracula” — probably it is a better investment.

Have you seen that a newer Pawn Stars episode in 2019 featured another vampire kit supposedly owned by Phillip Burne-Jones, which Rick purchased for $16,000?

Pawn Stars – Season 16 Episode 3 – Pawn Of The Undead

I found your website because I was looking at a vampire kit cabinet. It is a tall gothic cabinet with items for killing vampires inside. Looking at each of the pieces, they do look to be antique, but apparently there are people that go to great extent to create aged looking pieces, or find antique pieces and put them in the kits. I had never seen these in a cabinet before. I have been considering purchasing this after seeing the newest Pawn Stars episode, but after reading your article, I’m now having second thoughts.