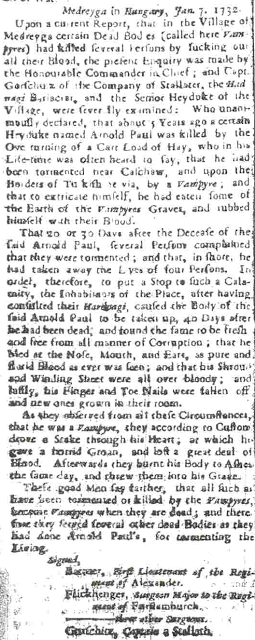

Upon a current Report, that in the Village of Medreyga certain Dead Bodies (called here Vampyres) had killed several persons by sucking out all their Blood, the present Enquiry was made by the Honourable Commander in Chief ; and Capt. Gorschutz of the Company of Stallater, the Hadnagi Bariacrar, and the Senior Heyduke [hajduk] of the Village, were severally examined : Who unanimously declared, that about 5 Years ago a certain Heyduke named Arnold Paul was killed by the Overturning of a Cart Load of Hay, who in his Life-time was often heard to say, that he had been tormented near Caschaw, and upon the borders of Turkish Servia [Serbia], by a Vampyre ; and that to extricate himself, he had eaten some of the Earth of the Vampyres Graves, and rubbed himself with their Blood.

And I was content knowing that this was the earliest appearance of the word, “vampire,” in English—until Nov. 12 when my friend, Lauri Löytökoski, sent me a link to a blog post by Ross Macfarlane, the Research Engagement Officer at the Wellcome Library, London.

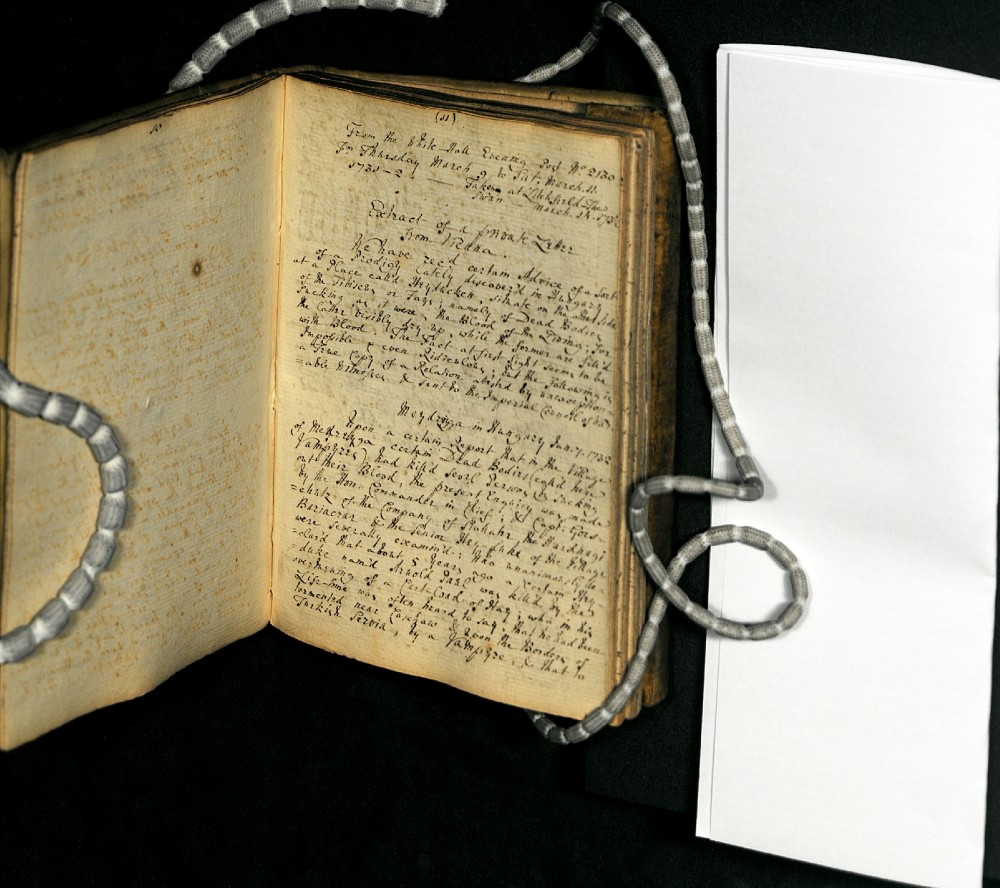

Lauri was sharing it with me for the hell of it, but didn’t realise the post’s significance to me—which I immediately grasped from its opening lines: “We have received certain Advice of a Sort of a Prodigy lately discovered in Hungary…namely of Dead Bodies Sucking, as it were, the blood of the living,” a quote attributed to the “Whitehall Evening Post, 9 March 1731-2 [1732].” If this citation is accurate, it beats the London Journal for the first English appearance of “vampire” by two days.

Macfarlane’s post does not mention the significance of this attribution, but when I raised it with him in an email he said: “Yup, although I didn’t state it in the article – though until re-reading it this morning I honestly thought I did! – I knew about the importance of this case.” But before we re-write the history books, there are two obstacles in the way of declaring the Whitehall Evening Post our winner for the first appearance of “vampire” in English.

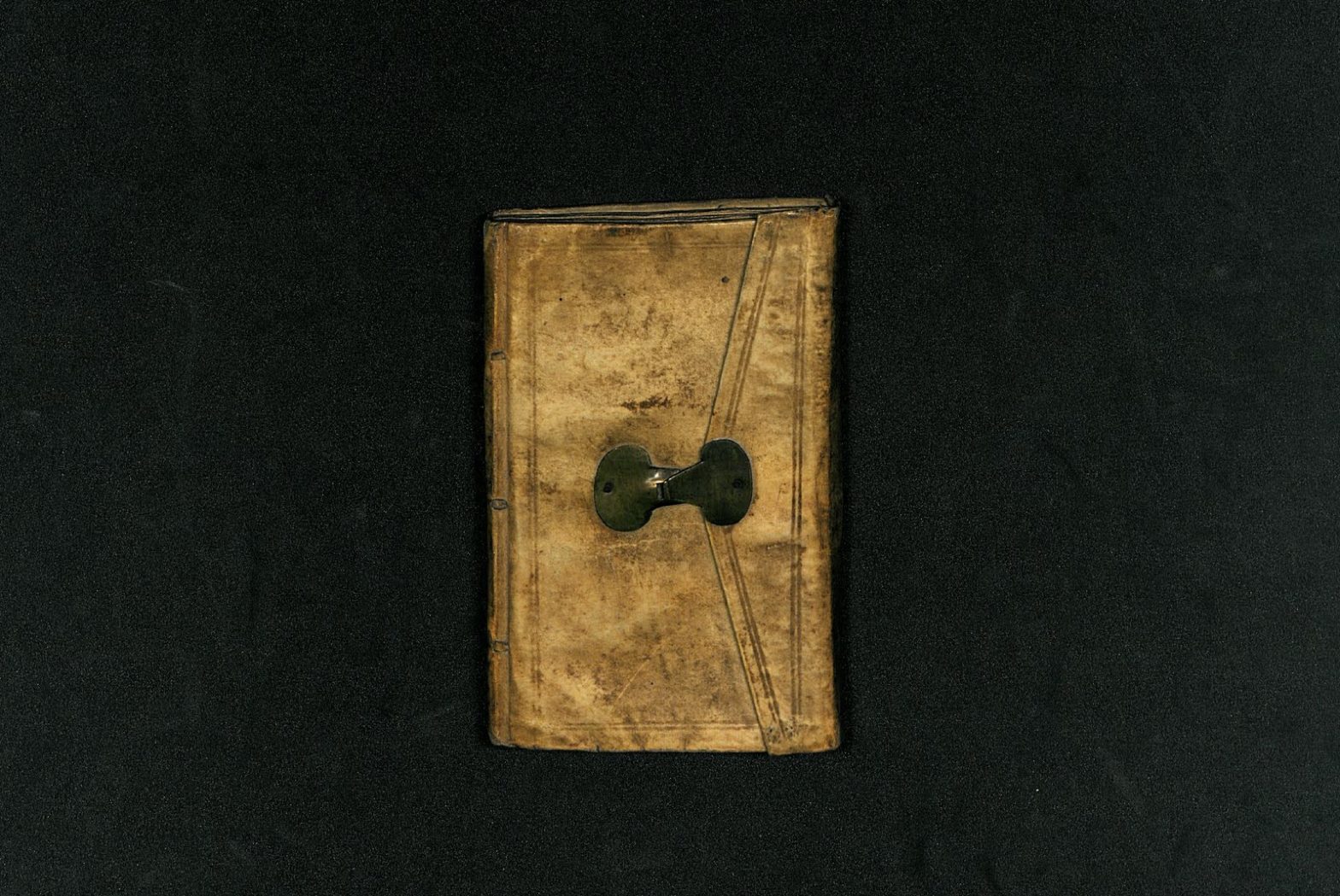

Firstly, Macfarlane’s quote is not from a primary source. The quote and citation used in his post is actually derived from the blog post’s subject: MS.2801, a handwritten manuscript in the Wellcome Library’s collection, dated between 1732–1742. The manuscript’s unnamed author was evidently a collector of “Strange events, accidents and phenomena” who jotted down accounts from newspapers.

The second obstacle is the paper’s date range, as listed in the manuscript: “Thursday March 9 to Sat. March 11. 1731–2 [1732],” and a possible transcription date of March 14, 1732. Articles from this period were sometimes headed by previous dates; for instance, the Grub-street Journal‘s coverage of the same case dated their report “Friday, March 10,” but the item was actually published in their March 16, 1732 issue. Could the same thing have happened here?

I can’t say for sure without double-checking the Whitehall Evening Post‘s March 9, 1732 issue, which has proven to be a decidedly difficult task. The British Library has copies of the Whitehall Evening Post in its 17th and 18th Century Burney Collection, which has been digitised and is available online to library members whose libraries have access to it. Unfortunately, the archive’s coverage for 1732 only extends to Jan. 25–27 and June 22–24.

I have also tried Lastchancetoread.com, NewspaperARCHIVE.com, the University of Birmingham, the State Library of New South Wales, the University of Sydney, the National Library of Australia, and the British Newspaper Archive. No luck yet, but the search will continue.

Notes:

- introduced to the English language through a news item: Anthony Hogg, “When Did Vampires Enter the English Language?” Diary of an Amateur Vampirologist (blog), June 3, 2009, accessed Nov. 13, 2015, http://doaav.blogspot.com.au/2009/06/when-did-vampires-enter-english.html. archive.is link: https://archive.is/jln0h.

- My source for this factoid was vampire expert, Jean Marigny: Jean Marigny, Vampires: The World of the Undead (London: Thames and Hudson, 1994), 48. Marigny’s book was originally published in French as Sang pour sang : Le réveil des vampires (Paris: Gallimard, 1993). The English version was translated by Lory Frankel.

- “Upon a current Report”: “Extract of a Private Letter from Vienna,” London Journal, March 11, 1732, [3].

- “called here Vampyres“: Some writers claim vampyre refers “real” (living) vampires whereas vampire refers to the creatures of folklore and fiction. In reality, there’s no difference between vampire and vampyre; the latter rendering is merely an archaic spelling of the same word. Anthony Hogg, “Vampire or Vampyre?” Diary of an Amateur Vampirologist (blog), Aug. 4, 2010, accessed Nov. 13, 2015, http://doaav.blogspot.com.au/2010/08/vampire-or-vampyre.html. archive.is link: https://archive.is/MHldn.

- a blog post by Ross Macfarlane: Ross Macfarlane, ” ‘A Vampyre in Hungary’ ,” Wellcome Library (blog), Oct. 31, 2010, accessed Nov. 12, 2015, http://blog.wellcomelibrary.org/2010/10/a-vampyre-in-hungary/. archive.is link: https://archive.is/38FHR.

- “Yup, although I didn’t state it in the article”: Ross Macfarlane, e-mail message to author, Nov. 12, 2015.

- dated between 1732–1742: “Wellcome Library Western Manuscripts and Archives Catalogue,” Wellcome Library, n.d., accessed Nov. 20, 2015, http://archives.wellcomelibrary.org/DServe/dserve.exe?dsqIni=Dserve.ini&dsqApp=Archive&dsqCmd=Show.tcl&dsqDb=Catalog&dsqPos=0&dsqSearch=%28AltRefNo%3D%27ms.2801%27%29. archive.is link: https://archive.is/ZFiAJ.

- “Strange events, accidents and phenomena”: Ibid.

- the Grub-street Journal‘s coverage of the same case: Grub-street [Grub Street] Journal (London), March 16, 1732, [2], 17th-18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers, accessed Nov. 20, 2015, available through the National Library of Australia.

Further Reading:

- Anthony Hogg, “Bite This!” The Vampirologist (blog), June 25, 2013, http://thevampirologist.blogspot.com.au/2013/06/bite-this.html. Refuting Kevin Jackson’s claim that the Gentleman’s Magazine featured the first appearance of “vampire” in English.

- Niels K. Petersen, “Visum et Repertum,” Magia Posthuma (blog), Sept. 20, 2008, http://magiaposthuma.blogspot.com/2008/09/visum-et-repertum.html. An excellent primer on the Arnold Paul case.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Lauri Löytökoski for sharing Ross Macfarlane’s blog with with me. Lauri has written an excellent English language essay on the Arnold Paul case called “Srpski Vampir,” which has been published in “Folk Horror Revival: Field Studies” (Wyrd Harvest Press, 2015), edited by Katherine Beem and Andy Paciorek.

The book also features an interview with Bob Curran and an essay by Tina Rath called “All You Ever Knew About Vampires Is Wrong: A Transcript of a Fortean Meeting Talk.” If that wasn’t enough to convince you to buy it, all profits made from the book will go to Wildlife Trust projects.