Andy Boylan’s article covering witch/vampire hybrids credits an example in a poem by Robert Southey (1774–1843) called “The Old Woman of Berkeley,” citing its publication date as 1798. Boylan previously used the same date for the poem in his vampire reference book The Media Vampire (2012). Other authors have also used the same publication date—but they are all mistaken.

Establishing the Right Publication Date

I discovered their error while seeking an “originally published in” credit for Boylan’s citation of the poem via its publication on HorrorMasters.com. Try as I might, I couldn’t establish the poem’s publication earlier than the second volume of Robert Southey’s Poems (1799) or its reproduction in a review of the book in The Monthly Visitor (May 1799).

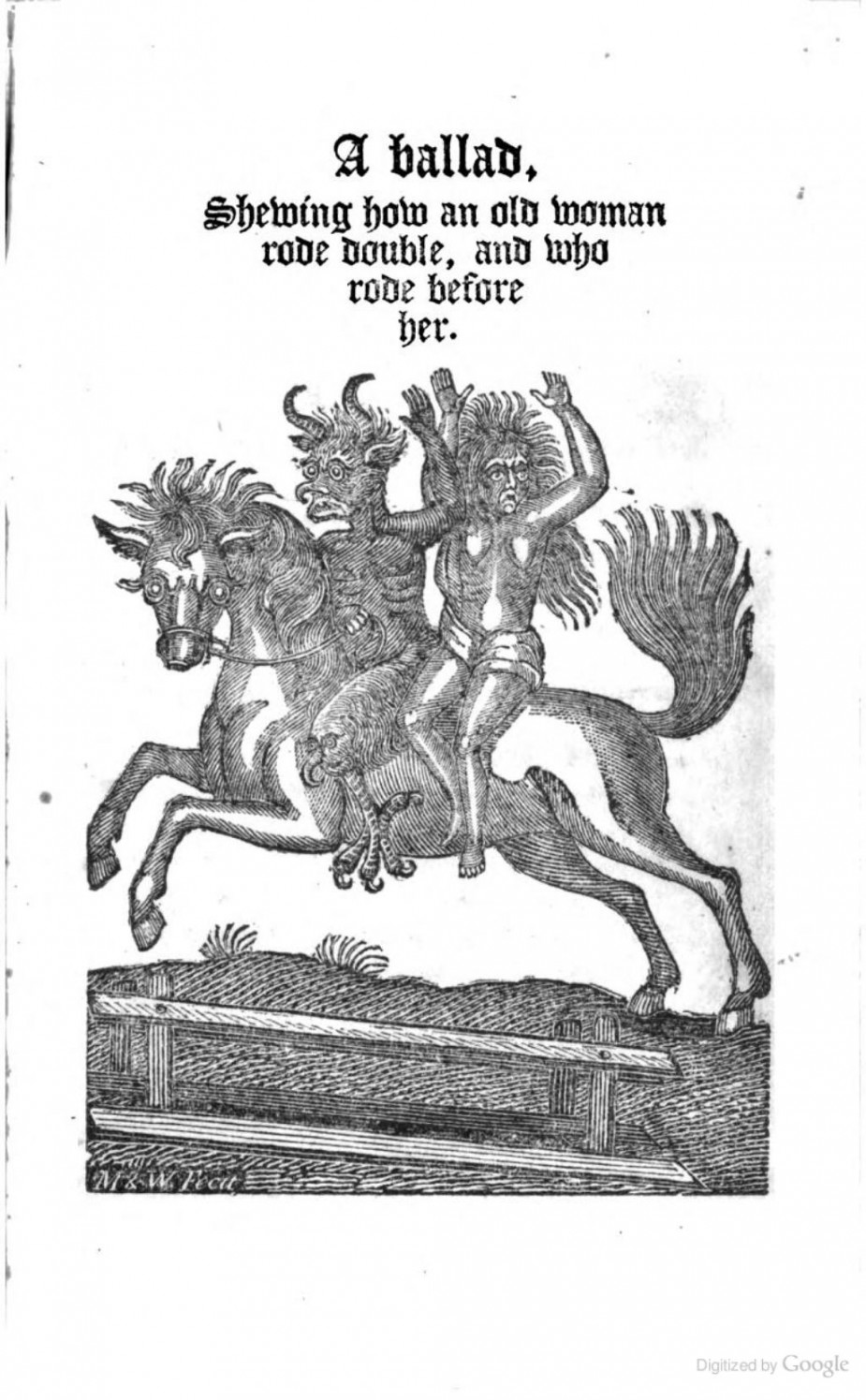

That’s when I made another discovery: “The Old Woman of Berkeley” wasn’t its original title. The version published in Poems is called “A Ballad, Shewing How an Old Woman Rode Double, and Who Rode Before Her,” the name appearing over a woodcut engraving preceding the poem. The same title—sans woodcut—is used for the poem’s appearance in the Monthly Visitor review.

The earliest version of the poem I could find with “The Old Woman of Berkeley” as its title was in the first volume of Tales of Wonder (1801), an anthology compiled by M. G. Lewis—best known for writing The Monk: A Romance (1796), a classic Gothic novel originally published in three volumes.

My search for the correct publication date was primarily conducted through Google Books, aided by its ability to narrow searches down to specific time frames. But how could I be sure 1799 was the right date? After all, the results for searches on Google Books are limited by what it has catalogued.

What if I was overlooking an obscure source not available there? To cast my net wider, I needed to expand my search to find a “smoking gun”—fortunately, one came to me through a Japanese website.

The Smoking Gun

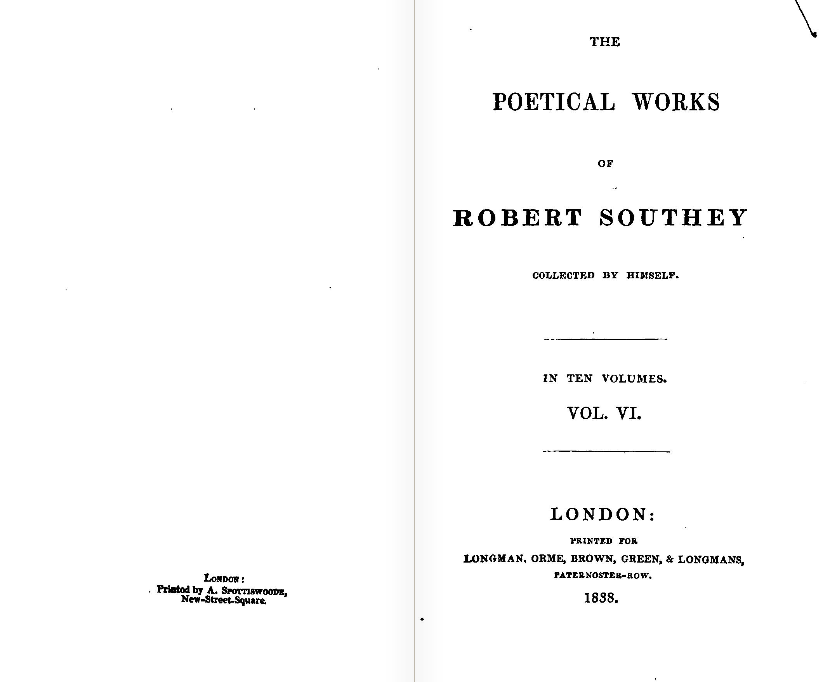

I found The British Literary Ballads Archive, the website in question, during Google searches for information on the poem. The website reproduces a copy of the poem as a pdf file. The reproduced poem’s source is credited as: “The Poetical Works of Robert Southey. Vol. 6. Collected by Himself. 10 vols. London, 1838″. I found the book on Internet Archive and “The Old Woman of Berkeley” within.

What I didn’t expect to find was Southey’s confirmation of the poem’s true publication date—which he mentions in the book’s preface:

Mr. Wathen [. . .] traced for me a facsimile of a wooden cut in the Nuremberg Chronicle [. . .] It represents the Old Woman’s forcible abduction from her intended place of burial. This was put into the hands of a Bristol artist; and the engraving in wood which he made from it was prefixed to the Ballad when first published, in the second volume of my poems 1799.

The woodcut engraving preceding “A Ballad, Shewing How an Old Woman Rode Double, and Who Rode Before Her” in Poems, vol. 2 (1799) matches Southey’s description.

To be fair, Boylan’s quotation at least originates from Southey, who rejigged the original line to “From sleeping babes I have suck’d the breath” in the version of the poem published in The Poetical Works of Robert Southey: Collected by Himself, vol. 6 (1838).

Southey even changed the poem’s title in that book to a merger of two previous titles as confirmed in the fifth volume of Robert Southey: Poetical Works 1793–1810 (2004)—along with other changes:

Included in Poems (1800) [sic] and revised for Poems (1806). Published with amendments in Minor Poems [of Robert Southey] (1815, 1823) and revised and retitled ‘The Old Woman of Berkeley, A Ballad, Shewing How An Old Woman Rode Double, And Who Rode Before Her’ in PW [Poetical Works of Robert Southey: Collected by Himself] (1837–8) [vol. 6, 1838].

So, why have many authors, including Boylan, mistakenly cited the poem’s publication date as 1798? The most likely explanation is a peculiar amendment attached to reprints of the poem.

Why Authors (Mistakenly) Think the Poem Was First Published in 1798

When the poem initially did the rounds in other books, there were no accompanying references to its publication date. But that changed when “1798” began being amended to the end of the poem; the earliest example I’ve found features in the third volume of The Minor Poems of Robert Southey (1815). Other compilers followed suit.

As it happens, Southey was one of them. Despite clarifying the poem was originally published in 1799 in the preface to The Poetical Works of Robert Southey: Collected by Himself, vol. 6 (1838), he amended “Hereford, 1798″ to the end of the poem in the same volume. But this was clearly intended to represent the place and year it was written, not published.

In fact, Southey discusses the poem’s composition at length in his preface to the book, clarifying “In the autumn of the same year [1798], I passed some days at Hereford with Mr. William Bowyer Thomas [d. 1802]” who helped Southey gain access to “the books in the Cathedral Library”.

Although the cathedral isn’t named, Southey’s presence in Hereford and his reference to being holed up in an area of the cathedral where “the books were kept in chains” suggests he was visiting The Chained Library at Hereford Cathedral, or, to give its proper title, The Cathedral Church of St Mary the Virgin and St Ethelbert the King.

Whichever place it was, while in the library, Southey “first read the story of the Old Woman of Berkeley, in Matthew of Westminster [Flores Historiarum] and transcribed it into a pocket-book,” adding:

the circumstantial details in the monkish Chronicle impressed me so strongly, that I began to versify them that very evening. It was the last day of our pleasant visit at Hereford; and on the following morning the remainder of the Ballad was pencilled in a post-chaise on our way to Abberley.

Southey also mentions that the inspiration for his poem’s woodcut, an illustration in the Nuremberg Chronicle, was “among the prisoners in the Cathedral” meaning that if both books are present there, the likelihood of Southey’s visit increases tenfold.

In the meantime, conclusive evidence of the poem’s composition in 1798 comes to us through contemporary correspondence, which reveal Southey had finished the poem that year, making relatively minor tweaks along the way.

In a letter dated Oct. 1, 1798, Southey sent a copy of the poem to William Taylor (1765–1836), mentioning “the story is in Matthew of Westminster, & in Olaus Magnus [Historia de Gentibus Septsentrionalibus (1555)] – but it was the mere mustard seed, that has grown up into what you see.”

In another letter, dated Oct. 5, 1798, Edith Fricker Southey (1774–1837), Robert’s wife, copied the poem on Robert’s behalf to his brother, Thomas Southey (1771–1838). Robert also sent the poem to Charles Watkin Williams Wynn (1775–1850) in a letter dated Oct. 29, 1798.

Allusions to the poem’s woodcut engraving, which Robert made in another letter to his brother Thomas, dated Jan. 5, 1799, show the poem had not yet been published until its inclusion in Poems, vol. 2 (1799):

The Old Woman of Berkeley cuts a very respectable figure on horseback, & Beelzebub is so well admirably drawn that one would have suppose he had sat for his picture. I shall pass the next week in town & hurry out the volume. I have been obliged to suffer the printers delay because I had not time to furnish him with copy.

So, if you’re ever presented with conflicting publication dates, always try and find the original publication—don’t rely solely on reprints. If possible, follow a paper trail through reprints and references until you establish a conclusive source.

It’s sometimes hard work, but the end result pays dividends for your credibility, benefiting both your writing and other writers relying on your work as a reliable source of information.

Notes:

- Andy Boylan’s article covering witch/vampire hybrids: Andy Boylan, “No, Witchula Will Not Be the First Witch/Vampire Hybrid Film,” Vamped, Jan. 11, 2016, accessed Jan. 11, 2016, http://vamped.org/2016/01/11/no-witchula-will-not-be-the-first-witch-vampire-hybrid-film/.

- Boylan previously used the same date in his vampire reference book: Andrew M. Boylan, The Media Vampire: A Study of Vampires in Fictional Media (n.p.: Andrew M. Boylan, 2012), 17, 352, accessed Jan. 12, 2016, https://books.google.com.au/books?id=zvbQAwAAQBAJ.

- Other authors have also used the same publication date: E. Cobham Brewer, Character Sketches of Romance, Fiction and the Drama, ed. Marion Harland, vol. 4 (New York: Selmar Hess, 1896), 330; Susanne Fusso, Designing Dead Souls: An Anatomy of Disorder in Gogol (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993), 92; Patrick Waddington, From the Russian Fugitive to the Ballad of Bulgarie: Episodes in English Literary Attitudes to Russia from Wordsworth to Swinburne (Oxford: Berg, 1994), 48. Diane Long Hoeveler takes it a step further, claiming 1802 as the poem’s publication date in “Gothic Ballads” entry for The Encyclopedia of Romantic Literature, gen. ed. Frederick Burwick, vol. 1 (Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 505. These examples sourced through Google Books.

- the second volume of Robert Southey’s Poems: Robert Southey, Poems, vol. 2 (Bristol: Printed by Biggs and Cottle, for T. N. Longman and O. Rees, 1799), 149–60, accessed Jan. 11, 2016, https://books.google.com.au/books?id=2b_TAAAAMAAJ.

- a review of the book: A Society of Gentlemen, review of Poems, vol. 2, by Robert Southey, The Monthly Visitor, and Pocket Companion, vol. 7 (London: Printed for H. D. Symonds, 1799), 92–8, accessed Jan. 17, 2016, https://books.google.com.au/books?id=p9ARAAAAYAAJ. The poem appears on pp. 93–8.

- the first volume of Tales of Wonder: M. G. Lewis, Tales of Wonder, vol. 1 (London: Printed by W. Bulmer and Co., 1801), 164–74, accessed Jan. 11, 2016, https://books.google.com.au/books?id=DrACAAAAYAAJ.

- The British Literary Ballads Archive hosts a copy of the poem: Robert Southey, “The Old Woman of Berkeley: A Ballad, Shewing How an Old Woman Rode Double, and Who Rode Before Her,” accessed Jan. 11, 2016, http://literaryballadarchive.com/PDF/Southey_10_Old_Woman_of_Berkeley.pdf.

- I found the book on Internet Archive: Robert Southey, The Poetical Works of Robert Southey: Collected by Himself, vol. 6 (London: Printed for Longman, Orme, Brown, Green & Longmans, 1838), accessed Jan. 11, 2016, https://archive.org/details/poeticalworksro04soutgoog. The poem is found on pp. 174–83.

- “Mr. Wathen [. . .] traced for me a facsimile of a wooden cut in the Nuremberg Chronicle”: Ibid., xiv.

- Boylan quotes a line from the poem: Quoted in Boylan, “No, Witchula Will Not Be the First Witch/Vampire Hybrid Film.”

- “we can take the sucking of breath as being a description of energy vampirism”: Ibid.

- “I have suck’d the breath of sleeping babes”: Southey, Poems, 151.

- “From sleeping babes I have suck’d the breath”: Southey, Poetical Works of Robert Southey: Collected by Himself, 177.

- “The Old Woman of Berkeley, a Ballad, Shewing How an Old Woman Rode Double, and Who Rode Before Her”: Ibid., 174.

- the third volume of The Minor Poems of Robert Southey: The Minor Poems of Robert Southey, vol. 3 (London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1815), 207, accessed Jan. 12, 2016, https://books.google.com.au/books?id=6zNiAAAAcAAJ. Perhaps apropos to this article, Google Books has mistakenly rendered the book’s title “The Minor Problems of Robert Southey.” archive.is link: http://archive.is/Ucyuv. I have contacted them (Feb. 5, 2016) to fix it.

- Other publications followed suit: The Poetical Works of Robert Southey: Complete in One Volume (Paris: A and W Galignani, 1829), 663, accessed Jan. 12, 2016, https://books.google.com.au/books?id=3JAiAAAAMAAJ.

- “Hereford, 1798″: Southey, Poetical Works of Robert Southey: Collected by Himself, 183.

- the fifth volume of Robert Southey: Poetical Works 1793–1810: Selected Shorter Poems c. 1793–1810, ed. Lynda Pratt, vol. 5 of Robert Southey: Poetical Works 1793–1810 (London: Pickering and Chatto 2004), 293, accessed Feb. 5, 2016, https://books.google.com.au/books?id=6RZXAAAAYAAJ.

- “In the autumn of the same year”: Southey, Poetical Works of Robert Southey: Collected by Himself, xxi.

- “the books in the Cathedral Library”: Ibid.

- “the books were kept in chains”: Ibid.

- The Chained Library at Hereford Cathedral: “The Chained Library,” Hereford Cathedral, 2009, accessed Feb. 6, 2016, http://www.herefordcathedral.org/visit-us/mappa-mundi-1/the-chained-library. archive.is link: http://archive.is/MP2VB. I’ve e-mailed the cathedral’s website (Feb. 6, 2016) to double-check my suppositions and am presently awaiting a response.

- “first read the story of the Old Woman of Berkeley”: Southey, Poetical Works of Robert Southey: Collected by Himself, xxi.

- “the circumstantial details in the monkish Chronicle”: Ibid.

- “among the prisoners in the Cathedral”: Ibid., xiv.

- a letter dated Oct. 1, 1798: Robert Southey to William Taylor, Oct. 1, 1798, in The Collected Letters of Robert Southey, Part Two: 1798–1803, ed. Ian Packer and Lynda Pratt, August 2011, Romantic Circles, accessed Feb. 6, 2016, https://www.rc.umd.edu/editions/southey_letters/Part_Two/HTML/letterEEd.26.350.html. achive.is link: http://archive.is/HYEkP

- “the story is in Matthew of Westminster”: Ibid.

- another letter, dated Oct. 5, 1798: Robert Southey and Edith Southey to Thomas Southey, Oct. 5, [1798], in The Collected Letters of Robert Southey, Part Two: 1798–1803, ed. Ian Packer and Lynda Pratt, August 2011, Romantic Circles, accessed Jan. 12, 2016, https://www.rc.umd.edu/editions/southey_letters/Part_Two/HTML/letterEEd.26.351.html. achive.is link: https://archive.is/XWVP6

- a letter dated Oct. 29, 1798: Robert Southey to Charles Watkin Williams Wynn, Oct. 29, 1798, in The Collected Letters of Robert Southey, Part Two: 1798–1803, ed. Ian Packer and Lynda Pratt, August 2011, Romantic Circles, accessed Jan. 12, 2016, https://www.rc.umd.edu/editions/southey_letters/Part_Two/HTML/letterEEd.26.354.html. achive.is link: https://archive.is/xpqdG

- another letter to his brother Thomas, dated Jan. 5, 1799: Robert Southey to Thomas Southey, Jan. 5, 1799, in The Collected Letters of Robert Southey, Part Two: 1798–1803, ed. Ian Packer and Lynda Pratt, August 2011, Romantic Circles, accessed Feb. 5, 2016, https://www.rc.umd.edu/editions/southey_letters/Part_Two/HTML/letterEEd.26.369.html. archive.is link: http://archive.is/f54ro

- conflicting publication dates: While researching this article, I came across other authors who had correctly attributed the poem’s publication date as 1799. Therefore, my “find” isn’t new, but a document of my personal discoveries. Apart from Patrick Spedding (see “Further Reading”), other examples include: Lieselotte E. Kurth-Voigt, “La Belle Dame Sans Merci: The Revenant as Femme Fatale in Romantic Poetry,” in European Romanticism: Literary Cross-Currents, Modes, and Models, ed. Gerhart Hoffmeister (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1990), 250; Diana Greene, Reinventing Romantic Poetry: Russian Women Poets of the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), 72; Melissa Edmundson, “Avenging Angel: The Social Supernatural in Nineteenth Century British Women’s Writing” (Ann Arbor: ProQuest, 2007), 25. All examples sourced through Google Books.

- follow a paper trail: Anthony Hogg, “The Importance of Paper Trails,” Diary of an Amateur Vampirologist (blog), Sept. 1, 2010, accessed Feb. 5, 2016, http://doaav.blogspot.com.au/2010/09/importance-of-paper-trails.html. archive.is link: http://archive.is/ph0NO.

Further Reading:

Patrick Spedding, a lecturer in Literary Studies and am Associate-Director of the Centre for the Book, in the School of Languages, Literatures, Cultures and Linguistics, at Monash University, Melbourne, has written several interesting—and highly recommended—posts about “The Old Woman of Berkeley” on his self-titled blog:

- “The Witch of Berkeley: Devotee of Gluttony and Wantonness,” Patrick Spedding (blog), Jan. 11, 2015, http://patrickspedding.blogspot.com.au/2015/01/the-witch-of-berkeley-devotee-of.html.

- “De Castigatione Maleficarum; Or: The Punishment of Witches,” Patrick Spedding (blog), Jan. 14, 2015, http://patrickspedding.blogspot.com.au/2015/01/de-castigatione-maleficarum-or.html.

- “Southey’s Ballad on The Witch of Berkeley, 1799,” Patrick Spedding (blog), Jan. 15, 2015, http://patrickspedding.blogspot.com.au/2015/01/southeys-ballad-on-witch-of-berkeley.html.

Fair find, though his poem was written and shared in the earlier date as you mention.

I see little controversy in the change of the line, after all Southey changed it himself and the substance is the same.

Nevertheless good find, that will be reflected in the 2nd edition of the Media Vampire

It was, yes, but if we went by that principle, then the written/made dates for all things should be used too. For instance, “Nosferatu” — its copyright date is 1921, but it was released on March 4, 1922. Why not use the 1921 date? And so on.

I see little controversy in the changed line, too, which is why I said a “perceivable error” over an established one; if the original line quoted is intended to be the first instance, it isn’t. The original rendering in “Poems” is.

But thank you, I certainly look forward to the upcoming edition!