In the previous instalment, “5 Reasons a Wampyr Didn’t Walk in Highgate Cemetery” (Feb. 27, 2015), I discussed major topographical errors in Sean Manchester’s book The Highgate Vampire: The Infernal World of the Undead Unearthed at London’s Famous Highgate Cemetery and Environs (1985; rev. ed. 1991).

It took three months to complete that article (Chapman 2015b) and another three months to finish up this one. Anthony and I had just scratched the surface and discovered other holes in Manchester’s story. For instance, did you know…

#5. The Vampire Wasn’t a Topic in the Local Press—Until Manchester Made It One

During the course of Manchester’s supposed investigation into the Highgate Vampire, he decided to step forward and inform the local populace—albeit very reluctantly—about the threat posed to them (Manchester 1985, 45):

The time had come to confront them [the public] with this revelation [the vampire theory] so that those already under the fatal malignity could be reached and helped. How many I wondered were keeping this undead nourished? The only way I could reach all the people in the area was to make public my opinion and some of the facts leading up to it. This I did with a certain amount of reluctance as most forms of publicity put investigations of this kind into considerable risk. However, as it was already a topic in the local press, I felt that further harm would be minimal.

Manchester’s revised edition upgrades “topic” to a “major topic” (Manchester 1991, 69). There’s just one catch—the vampire didn’t become a topic until Manchester made it one in the same article (“Does a Wampyr Walk in Highgate?” 1970):

WE DON’T want to frighten you, but the ghost of Highgate Cemetery might be . . . a vampire.

So says . . . Sean Manchester, president of the British Occult Society. He claims to have carried out “extensive research and investigation into the matter.”

The ghost in question was first reported by David Farrant in a letter to the editor published in the Ham & High on Feb. 6, 1970 (Farrant 1970a):

SOME NIGHTS I walk home past the gates of Highgate Cemetery.

On three occasions I have seen what appeared to be a ghost-like figure inside the gates at the top of Swains Lane. The first occasion was on Christmas Eve. I saw a grey figure for a few seconds before it disappeared into the darkness. The second sighting, a week later, was also brief.

Last week the figure appeared, only a few yards inside the gates. This time it was there long enough for me to see it much more clearly, and now I can think of no other explanation than this apparition being supernatural.

I have no knowledge in this field and I would be interested to hear if any other readers have seen anything of this nature.

Manchester alludes to Farrant’s letter in his book; his quote from an uncredited “report” about a “ghost-like” figure seen three times at Highgate Cemetery (Manchester 1985, 41) is actually Farrant’s letter.

The Ham & High’s letter column between Feb. 13–27, 1970 was overrun by people commenting on Farrant’s ghostly encounters or sharing their own ghostly tales—but none mentioned a vampire. Interestingly, many respondents to Farrant’s letter were acquaintances or friends of Farrant and Manchester, though neither of them disclosed their connection at the time (Swale 2014).

Farrant wrote a follow-up letter reaffirming his ghostly sightings, published in the Feb. 27, 1970 issue: “You can imagine how relieved I was to discover by the response in the letter columns that I am not alone in witnessing the spectre that haunts Swains Lane.” (Farrant 1970b) However, as folklorist Bill Ellis notes: “the most impressive detail is the sheer amorphousness of the Highgate traditions” (1993, 22).

In other words, the sightings were characterised by their lack of consistency. Although a single term, “ghost,” was used for a supposed entity, descriptions varied from “a woman in the porch” (Berger 1970) to “a ghostly cyclist” (Baker 1970).

Far from beginning as a “major topic in the local press,” the vampire topic kicked off only when Manchester stepped forward with his theory—making him the topic’s originator, not ruminations in the local press.

Until Manchester sprung his vampire theory on the local populace, the local press’s coverage of supernatural activity—specifically of a ghost—had been regulated to the letters column. But the vampire pushed the ghost to the front page while edging it out at the same time (“Why Do the Foxes Die?” 1970): “THE mysterious death of foxes in Highgate Cemetery was this week linked with the theory that a ghost seen in the area might be . . . a vampire.”

We’ll discuss those dead foxes shortly. In the meantime, it’s clear Farrant was happy to let his ghost morph into a vampire. Here’s what Farrant said in the same article:

“Much remains unexplained, but what I have recently learnt all points to the vampire theory being the most likely answer.

“Should this be so, I for one am prepared to pursue it, taking whatever means might be necessary so that we can all rest.”

The Ham & High’s letter column began to reflect the topic change with discussions on the vampire seeping into discussions on ghosts. The vampire theory secured national coverage when reporter Sandra Harris was dispatched to interview Manchester and Farrant for ITV’s Today program. The program’s coverage, and the story’s vampire angle, ensured a third front page story in the Ham & High called “The Ghost Goes . . . on TV” (March 13, 1970): “Also interviewed was Mr. Sean Manchester, 25-year-old president of of the British Occult Society, whose theory is that it is not a ghost at all but . . . a vampire.”

The program’s broadcast triggered the infamous mass vampire hunt at Highgate Cemetery later that night. The following week, the Ham & High published a fourth front page story on the vampire, when a mail order clerk named Barry Edwards stepped forward claiming he was the vampire everyone had been searching for (“‘I WAS THE VAMPIRE'” 1970): “He explained that he was filming for an amateur cine group, the Hellfire Film Club, in Highgate Cemetery five weeks ago . . . as a vampire, complete with cape and a full set of shining canines.”

Manchester followed Edwards’ revelation with his own thoughts in the same article, amalgamating his vampire with Farrant’s “grey” ghost: “[Manchester] said that many of the sightings do not coincide with the club’s activities at the cemetery, and the black figure of Mr. Edwards does not fit the description of ‘the greyish figure moving silently.'” Adding: “I am really surprised at the interest taken in a possible ghost story.”

Manchester’s statement seems incredibly facetious considering he was the vampire story’s progenitor and actively courted press coverage, not to mention witnessing his story’s growth and spread through the Ham & High; incidentally, the only “local press” that covered the story until Today turned its cameras on the cemetery.

However, it’s hard to tell whether Manchester anticipated the hysteria of the mass vampire hunt; there’s no reliable indication that he intended it to get that out of hand. Either way, the event was enough to cement the vampire’s place in history, especially when the story gained international coverage through articles like “Horror Film Club Hoax Sparks a ‘Vampire’ Hunt” (Palm Beach Daily News, March 17, 1970).

#4. The Camera Director’s Fainting Wasn’t So Mysterious

On Friday, March 13, 1970 Sean Manchester was interviewed by Sandra Harris, for Thames Television’s news program Today. He gave Harris a tour of the Circle of Lebanon before filming at the North Gate—and that’s when “all hell broke loose” (Manchester 1985, 49–50):

Sandra began by asking questions about the vampire. But something was wrong. There was a strange noise interfering with the sound a technician said. We tried again. But it was to no avail; the eerie noises only grew worse. Suddenly, the camera director fainted and fell to the ground. Then it seemed as if all hell broke loose. The wind literally howled and screamed through the trees; wires running from the generator van lashed the icy ground and Sandra’s notes flew all over the place. The man who had collapsed was carried by members of the camera crew to a nearby van and rushed to hospital. Curiously, he had no previous history of fainting and no reason for this collapse was ever discovered. I asked Miss Harris whether she thought all this to be merely coincidental. She could not discount the possibility that it was not. Further attempts to shoot the interview by the north gate were abandoned and the actual interview took place outside the main gate further down Swains Lane.

Did this actually happen? On Dec. 3, 2014 I emailed Sandra Harris (now Sandra Harris Ramini): “Do you remember if the camera man actually fainted? Also were there some strange sounds that interfered with the filming causing you to move the location from the North Gate?”

Later that day she responded:

Yes, the camera man did faint, but he was quite old, had heart trouble and he had quite a vivid imagination. The strange sounds turned out to be ‘whoooo, whooos’ from the amateur actors in their sheets or whatever. But it suited our story to make it a bit more dramatic than it was . . . but I have no doubt it was earthly sylphs, nothing super natural.

Harris’ version of events certainly puts a damper on the spooky ambiance Manchester was striving to convey in his book.

#3. Manchester Downplayed Rational Explanations for Animal Deaths

Let’s circle back to the dead foxes found at Highgate Cemetery. The weekend after Manchester broadcast his vampire theory in the Hampstead & Highgate Express, the Ham & High carried a front page story discussing Farrant’s alleged discovery of a dead fox near the area he’d seen his ghost, adding (“Why Do the Foxes Die?” 1970):

“Several other foxes have also been found dead in the cemetery,” he said at his home in Priestwood Mansions, Archway Road, Highgate. “The odd thing is there was no outward sign of how they died.”

In the same article, Manchester said: “These incidents are just more inexplicable events that seem to complement my theory about a vampire.” However, an unnamed cemetery spokesperson quoted in the same article disagreed with both: “There are plenty of live foxes here. I’ve never seen a dead one.”

Manchester’s cautious tone went out the window by the time he related the incidents in his book, fifteen years later (Manchester 1985, 44):

Dead animals, notably nocturnal ones, kept appearing in Waterlow Park and Highgate Cemetery itself. Further inspection revealed what they all had in common were lacerations around the throat and they were completely drained of blood.

Manchester doesn’t reveal who inspected them, but added (Manchester 1985, 45):

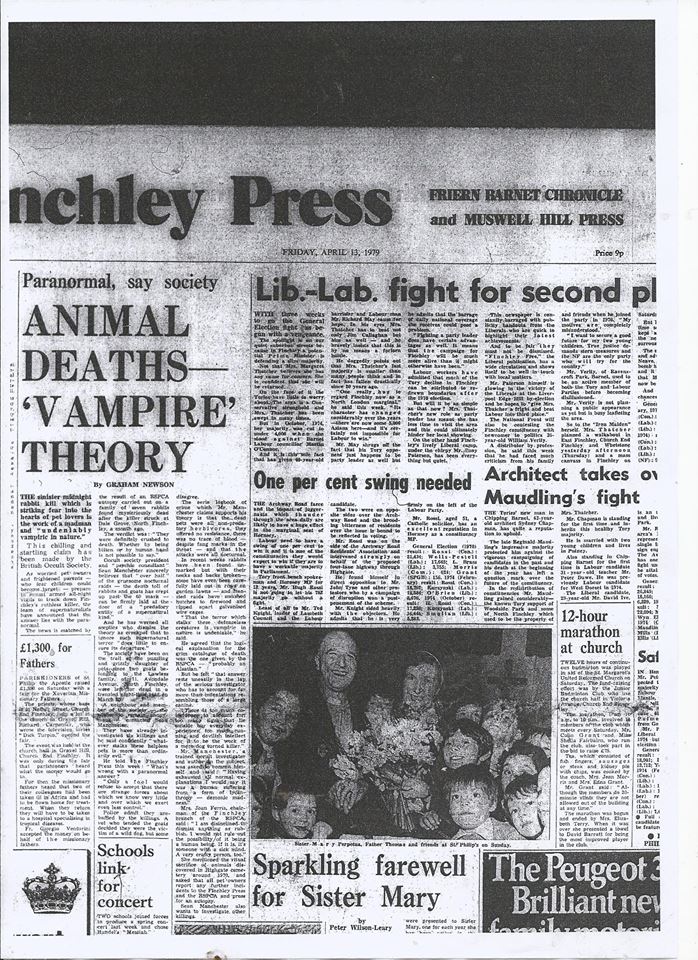

A similar outbreak of animal deaths in neighbouring Finchley some 9 years later had the benefit of an RSPCA [Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals] autopsy which revealed fang marks in the throat of the victims which were drained of blood. The Finchley Press, 13th April, 1979, reported: “Mrs Jone [sic, Joan] Ferris, chairman of the Finchley branch of the RSPCA, said, “I am disinclined to dismiss anything as rubbish. I would not rule out the possibility of it being a human being. If it is, it’s someone with a sick mind. A very crafty person too.”

She mentioned the ritual sacrifice of animals discovered in Highgate Cemetery around 1970, and asked that all pet owners report any further incidents.

However, the dead animals are given significantly less coverage in the revised edition of his book (Manchester 1991, 69):

Dead animals, notably nocturnal ones, were discovered scattered about Waterlow Park and the graveyard itself. Inspection revealed lacerations to the throat. All were completely drained of blood. Later outbreaks of animal deaths would benefit from an RSPCA autopsy which revealed fang marks in the throat of the victims and the total absence of blood.

As you can see from this passage, Manchester merged two separate incidents into one. Finchley is four miles from Highgate; an autopsy was done, but in Finchley, not Highgate—and nine years later. There’s no concrete way to connect the two incidents, proving Manchester’s statements are misleading and falsifying evidence so I am factoring the uncited report out of the equation.

So let’s focus on a keyword Manchester used in both editions: “lacerations.” This was an interesting word choice since when linked to his reference to a different wound in a photo captioned “The controversial punctures on the neck of Elizabeth Wojdyla,” referring to an attack by the Highgate Vampire (Manchester 1985, 73).

Although Manchester was clearly equating these marks as symptomatic of a vampire attack, lacerations and puncture wounds aren’t actually the same thing (Kahn 2014):

A cut (also called a laceration) is a tear or opening in the skin caused by an external injury. It can be superficial, affecting only the surface of your skin or deep enough to involve tendons, muscles, ligaments, and bone.

A puncture wound is a deep wound caused by something sharp and pointed, like a nail. The opening on the skin is small, and the puncture wound may not bleed much [. . .] Puncture wounds caused by a bite or stepping on a rusty piece of metal, like a nail, need prompt medical attention. Although puncture wounds don’t normally bleed heavily, they are prone to infection.

If the vampire used its fangs to bite the animals, as Manchester suggests, the wounds would be puncture marks, not lacerations. Manchester neglects to offer an alternate explanation for these wounds in his text, including strong possibilities like dogs, badgers or even another fox. After all, back in the 1970s Highgate Cemetery was an overgrown mess; and inhabited by a colony of wily urban foxes (“Highgate Cemetery” 2008).

But if Manchester’s “lacerations” were accurate, they could have been inflicted on the dead animals by other means—sharp objects, like knifes. This leads to another possibility: what if the lacerations weren’t from a vampire or another animal, but a human being?

Manchester quotes Ms. Joan Ferris saying: “I would not rule out the possibility of it being a human being. If it is, it’s someone with a sick mind.” (Manchester 1985, 44) It’s somewhat unlikely the vampire would’ve stabbed its victims when it was already equipped with sharp teeth.

I tried reaching out to Joan Ferris during research for this article, but sadly found out she passed away from a contact in the Finchley RSPCA. However, I was able to obtain a copy of the Finchley Press article Manchester quoted from: Graham Newson’s “Animal Deaths—‘Vampire’ Theory” (April 13, 1979). The article paints a very different picture of the deaths that Manchester lets on in his book, despite selectively quoting from it.

Firstly, a variety of animals died within the area—and they died by different means. Rabbits and goats were the primary targets; the RSPCA autopsy in question specifically concerned seven rabbits in Dale Grove, North Finchley, which had “definitely been crushed to death. Whether by being bitten or by human hand is not possible to say.” (Newson 1979) Meanwhile, two goats had been killed in a “frenzied night-time raid” and elsewhere, rabbits were

found unmarked but with their necks and back broken—some have even been carefully laid out in rows on garden lawns — and frenzied raids have smashed hutches to firewood and ripped apart galvanized wire cages.

Though police were baffled by the animal attacks, “a vet who tended the goats decided they were the victim of a wild dog”. The vet’s theory had support from a surprising source. Though Manchester told Newson “That the terror which stalks these defenceless creatures is vampiric in nature,” yet Manchester “agreed that the logical explanation for the grim catalogue of death was the one given by the RSPCA — ‘probably an Alsatian.'” (Newson 1979)

Manchester omitted this concession out of both editions of his book; along his alternative theory: “Having exhausted all normal explanations I would say it was a human suffering from a form of lycanthropy — demonic madness.” (Newson 1979)

Werewolves. Great. We’ll go with the Alsatian theory instead.

#2. Manchester Blames the Vampire’s Presence on Satanists—With Zero Evidence

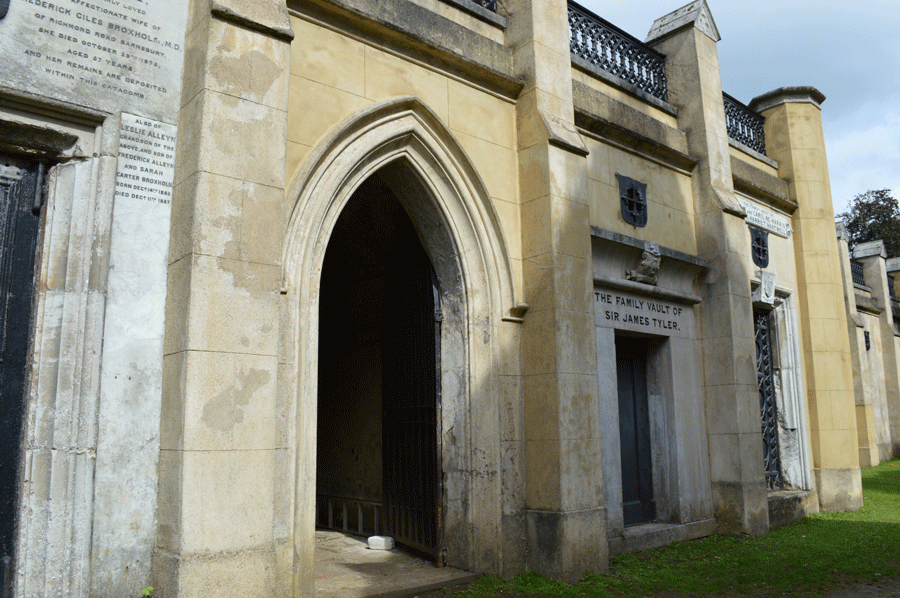

According to Manchester, Highgate Cemetery’s Terrace Catacombs were a focal point for Satanic activity (Manchester 1985, 44):

One thing which was uncovered by the considerable research being carried out at the time was evidence of the remains of a Satanic ceremony in the murky depths of the catacombs. This included pieces of burnt crucifixes, dried blood, splashes of black candle grease, and traces of a curious mixture which when analyzed turned out to be deadly nightshade, rue, myrtle covered in sulphur and alum, the majority of which had been burned.

Yet Manchester is less assured about the nature of activity in the catacombs in his revised edition, omitting references to “considerable research” and “a Satanic ceremony” (Manchester 1991, 69):

Remains of a weird ceremony in the murky depths of the catacombs were also discovered. Evidence included pieces of burnt crucifixes, dried blood, splashes of black candle grease and traces of a curious mixture which when analyzed turned out to be a deadly nightshade, rue, myrtle covered in sulphur and alum, the majority of which had been burned.

In both books, Manchester claims “a curious mixture which when analyzed.” What authority conducted the analysis of the mixture? Manchester didn’t think to mention such trivialities in his text. Nor does he explain how these burnt ingredients were correctly identified in the first place.

But what’s the significance of these ingredients? Though Manchester doesn’t explicitly say it, they’re recognisable as components used in a Satanic ceremony called a Black Mass (Howard 2002).

According to Manchester, ceremonies were being conducted “in an attempt by a body of satanists to resurrect the King Vampire” (“Does a Wampyr Walk in Highgate?” 1970).1 Manchester also infers another connection between the Satanic ceremonies and the vampire with another incident at the cemetery (Manchester 1985, 53):

The Hampstead and Highgate Express, 7th August, 1970, reported: The discovery of a headless body and signs of a Satanic ceremony have renewed fears of a vampire cult centred around Highgate Cemetery. A police spokesman said: “We are working on the theory that this may be connected with black magic. The body could well have been used for that reason.”

Manchester’s passage, a highly condensed version of what originally appeared in the article, omits mentioning the “vampire cult” theory was his own (“That Vampire Back Again?” 1970):

His [Manchester] conclusion: “These are the Satanists that desecrate Highgate cemetery [sic] are disciples of the ‘Evil One,’ the vampire, and intend to spread the cult in the hope of corrupting the world.”

He said the first step in “their abominable work” was to resurrect the “King Vampire of the Undead,” with the help of the powers of darkness, and, with his aid, increase their cult.

Convinced that the desecration was part of a secret Satanic meeting, Mr. Manchester has since exorcised the vault with an occult ceremony using crucifixes, candles, holy water and garlic.

A police spokesman said: “We are working on the theory that this may be connected with black magic. The body could well have been used for that reason.”

These elusive Satanists are presented as a constant bugaboo; a thorn in Manchester’s side (Manchester 1985, 86):

I was no less aware than today that tracking down the Satanists really responsible for increased black magic in north London would be a formidable task. The Highgate case showed clear evidence of the vampire’s living emissaries.

But by the time of the revised edition’s publication, the Satanists are downgraded: “The Highgate case had opened the lid to a particularly nasty can of worms and uncovered evidence of the vampire cult’s living emissaries: those who worship evil.” (Manchester 1991, 121)

It probably goes without saying that Manchester never catches any of the Satanists of “vampire cult’s living emissaries,” but Manchester doesn’t hold himself back from blaming them anyway (Manchester 1985, 90):

Since the cemetery was now publicly exposed as a focal point of inhuman devilry, there was no likelihood of the coffin remaining within its confines. It occurred to me that the old chapel might well have been the clandestine method of exit by the Satanists, as an almost forgotten passage leads from the chapel beneath Swains Lane to the newer graveyard founded in 1852. Existing originally for the discreet trans-portation of coffins from the chapel to the tombs on the other side of the lane, this subterranean tunnel might have provided an ideal escape route for the unholy convoy.

Lots of speculation; zero evidence. Manchester also failed to realise Black Masses aren’t used to “resurrect” vampires; they’re intended to mock God and worship the devil. As the Satansheaven website elaborates, the mass is (“The Black Mass n.d.):

a magical ceremony and inversion or parody of the Catholic Mass that was indulged in ostensibly for the purpose of mocking God and worshipping [sic] the devil; a rite that was said to involve human sacrifice as well as obscenity and blasphemy of horrific proportions.

And even if they were used to resurrect vampires, there’s no evidence they’d be successful at the task. Incidentally, the vault Manchester supposedly exorcised was the Family Vault of Charles Fisher Wace (Chapman 2015a); yet the Aug. 7, 1970 article makes no mention of the vampire’s supposed presence there, another classic example of Manchester’s evolving an often contradictory narrative.

#1. Manchester’s “Foreign Nobleman” Never Existed

The elusive vampire cultists have been part of Manchester’s narrative since he first told the story. And so has a particular residence (“Does a Wampyr Walk in Highgate?” 1970):

“[Manchester’s] theory is that the King Vampire of the Undead, originally a nobleman who dabbled in black magic in medieval Wallachia, “somewhere near Turkey,” walks again.

“His followers eventually brought him to England in a coffin at the beginning of the 18th century and bought a house for him in the West End,” said Mr. Manchester. “His unholy resting place became Highgate cemetery [sic].”

Firstly, Wallachia, a region of Romania, is nowhere near Turkey. But who was this mysterious nobleman, what was he doing in England and where is the mysterious “resting place”? Manchester provides further details in his book (Manchester 1985, 89):

St. Michael’s Church which overlooks the haunted catacombs of Highgate, is built on the site of a mansion [Ashurst House] once owned by Sir William Ashurst, Lord Mayor of London in 1694. The mansion was demolished in 1830 and its grounds now form the larger part of the cemetery. But after the death of Sir William in 1720 — at the height of the vampire epidemic which had its origins in south-east Europe — a nobleman came to these shores (transported in a coffin, according to one story I have been told by someone in the area) and leased the property which cast its shadow where now stands the Columbarium. From that time onwards there have been reports of strange incidents not unlike the outbreak at the turn of the seventies.

As established in the previous installment of this article, Manchester is referring to the Circle of Lebanon, not the Columbarium. Despite being unable to identify the “nobleman,” or clarifying exactly why he thought he was a vampire, Manchester (1985, 89):

felt it reasonable to surmise that the arrival of this European nobleman (in most odd circumstances according to one source) and the phenomenon’s commencement was more than just a coincidence. Moreover, being at a time when the undead pestilence was sweeping across the Continent, I felt justified in laying all the local trouble at the feet of this mysterious visitor who bore all the hallmarks of a vampire.

The “hallmarks” are left unexplained; the only vampiric qualifier Manchester bestows on him seems to be his foreign nobility.2 The revised edition of his book significantly cuts down the vampire’s backstory (Manchester 1991, 51):

He [William Ashurst] died in 1720 and the impressive three-storey mansion, known as Ashurst House, was sold and leased to a succession of tenants of whom one was a mysterious nobleman from the Continent who arrived in the wake of the vampire epidemic which had its origins in south-east Europe. Strange incidents began to haunt the area with reports of “hobbs, ghaists and daemons” abounding.

Despite these reports supposedly “abounding” during this period, Manchester didn’t provide a single example and I wasn’t able to trace any. However, I was able to trace the “succession of tenants” at Ashurst House—and there’s not a single “foreign nobleman” among them (Baggs et al. 1980):

The 1680s and 1690s saw new gentlemen’s houses on the south and west sides of the green, where attractive sites had been monopolized by Arundel House and Dorchester House. The Arundel House estate was sold in 1670 by Sir Robert Payne’s son William to Francis Blake, who divided the mansion and allowed his younger brother William to occupy the banqueting house farther west. Andrew Campion, a later purchaser, moved to a new residence, afterwards South Grove House, on the western part of his land in 1675. He sold the banqueting house itself to William Blake, who adapted it for his ill-fated Ladies’ Hospital. William Blake made way in 1681 for his son Daniel, who soon conveyed the property to his father’s creditor Sir William Ashurst, later lord mayor of London (d. 1720). Ashurst replaced the western part of Arundel House with Old Hall in the 1690s and also chose the site of the banqueting house for a grander residence. Ashurst House, sometimes called the Mansion House, impressed Defoe. It was a large square building set back from the green, at the end of an avenue later marked by the approach to St. Michael’s church, and commanded formal gardens stretching much farther down the hill than those of its neighbours. The house was sold by Sir William’s grandson William Pritchard Ashurst to John Edwards (d. 1769) and leased by Edwards’s descendants Sarah Cave and Sarah Otway Cave, whose tenants included the judge Sir Alan Chambré (d. 1823). After serving as a school, Ashurst House was bought as the site for a church in 1830.

Volume 17 of Survey of London (1936), edited by Percy Lovell and William McB. Marcham, elaborates on all tenants who resided in Ashurst House between 1674–1830 before the land was sold to H.M. Commissioners for Building New Churches (“Ashurst House” 1936).

Therefore it’s obvious Manchester’s “foreign nobleman” only existed in Manchester’s imagination. And if the nobleman was born there, it’s more than likely the vampire was too.

[su_spoiler title=”Notes”]1 Manchester denies using the term “King Vampire” in the article, citing it as a “Draculesque adornment preferred both by [folklorist Bill] Ellis and the journalist responsible for the front page press report” (Manchester 1997, 72).

2 This xenophobic attitude is not so surprising in light of recent revelations concerning Manchester’s penchant for Nazism (Chesham n.d.).[/su_spoiler]

[su_spoiler title=”References”]”Ashurst House and St Michael’s Church Monuments.” 1936. In Survey of London, edited by Percy Lovell and William McB. Marcham. Vol. 17, The Parish of St Pancras, Part 1: the Village of Highgate, 54–62. London: London County Council. Accessed April 21, 2015. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol17/pt1/pp54-62.

Baggs, A.P., Diane K. Bolton, M.A. Hicks, and R.B. Pugh. 1980. “Hornsey, Including Highgate: Highgate.” In A History of the County of Middlesex, edited by T.F.T. Baker and C.R. Erlington. Vol. 6, Friern Barnet, Finchley, Hornsey with Highgate, 122–35. London: Victoria County History. Accessed April 30, 2015. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol6/pp122-135.

Baker, Y. 1970. Letter to the editor. Hampstead & Highgate Express, Feb. 27, 10.

Berger, Pauline. 1970. Letter to the editor. Hampstead & Highgate Express, Feb. 27, 10.

“The Black Mass.” n.d. Satansheaven. Accessed April 13, 2015. http://www.satansheaven.com/black_mass.htm.

Chapman, Erin. 2014. “Seeking Vampires in London.” Vamped, Nov. 16. Accessed Dec. 6, 2014. http://vamped.org/2014/11/16/seeking-vampires-in-london/.

———. 2015a. “5 Reasons a Wampyr Didn’t Walk in Highgate Cemetery.” Vamped, Feb. 27. Accessed March 31, 2015. http://vamped.org/2015/02/27/5-reasons-why-a-wampyr-didnt-walk-in-highgate-cemetery/.

———. 2015b. “Cemetery Logistics: How I Tracked the Highgate Vampire.” Vamped, April 4. Accessed April 5, 2015. http://vamped.org/2015/04/04/cemetery-logistics-how-i-tracked-the-highgate-vampire/.

Chesham, Kevin. n.d. “Kevin Chesham – The Autobiography – First Extract.” Kevin Chesham – Triathlete. Accessed May 27, 2015. http://kevchesham.blogspot.co.uk/p/kevin-chesham-autobiography-first.html.

“Does a Wampyr Walk in Highgate?” 1970. Hampstead & Highgate Express, Feb. 27, 1.

Ellis, Bill. 1993. “The Highgate Cemetery Vampire Hunt: The Anglo-American Connection in Satanic Cult Lore.” Folklore 104 (1–2): 13–39.

Farrant, David. 1970a. “Ghostly Walks in Highgate.” Letter to the editor. Hampstead & Highgate Express, Feb. 6, 26.

———. 1970b. Letter to the editor. Hampstead & Highgate Express, Feb. 27, 10.

“The Ghost Goes… on TV.” 1970. Hampstead & Highgate Express, March 13, 1.

“Horror Film Club Hoax Sparks a ‘Vampire’ Hunt.” 1970. Palm Beach Daily News, March 17, 7. Accessed May 25, 2015. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1961&dat=19700317&id=A8stAAAAIBAJ&sjid=HJcFAAAAIBAJ&pg=4647%2C1993095&hl=en.

“Highgate Cemetery.” 2008. BBC. Last modified Oct. 27. Accessed Dec. 7, 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/london/content/articles/2005/05/10/highate_cemetery_feature.shtml.

Howard, Jim. 2002. “The Incense of the Black Mass in Huysmans’ La-Bas.” Synagoga Satanae, October. Accessed Dec. 14, 2014. http://www.angelfire.com/az3/synagogasatanae/incense.htm.

“‘I WAS THE VAMPIRE.'” 1970. Hampstead & Highgate Express, March 20, 1.

Kahn, April. 2014. “What Causes Puncture Wound? 6 Possible Conditions.” Medically reviewed by George Krucik. Healthline. Accessed Dec. 5, 2014. http://www.healthline.com/symptom/puncture-wound.

Manchester, Sean. 1985. The Highgate Vampire: The Infernal World of the Undead Unearthed at London’s Famous Highgate Cemetery and Environs. London: British Occult Society.

———. 1991. The Highgate Vampire: The Infernal World of the Undead Unearthed at London’s Highgate Cemetery and Environs. Rev. ed. London: Gothic Press.

———. 1997. The Vampire Hunter’s Handbook: A Concise Vampirological Guide. London: Gothic Press.

Newson, Graham. 1979. “Animal Deaths—‘Vampire’ Theory.” Finchley Press, April 13, 1.

Swale, Trystan. 2014. “The Highgate Vampire – An Exercise in Deception?” Mysterious Times, March 27. Accessed Dec. 13, 2014. http://mysterioustimes.wordpress.com/2014/03/27/the-highgate-vampire-an-exercise-in-deception/.

“That Vampire Back Again.” 1970. Hampstead & Highgate Express, Aug. 7, 1.

“Why Do the Foxes Die?” 1970. Hampstead & Highgate Express, March 6, 1.[/su_spoiler]

The reason why we had to blur Manchester’s photograph in this article will become readily apparent when you read “‘Vampire Hunter’ Hammers Stake Through Article.”

Dear readers,

It is quite, and decades long overdue obvious, that Farrant and Manchester originated the HighGate Cemetery “vampire” legend all by themselves. Of course hatred for each other would be noted so that their cute hoax would not give the evidence of their cooperation together in this.

So, now that anyone with an actual working, thinking brain blessed with reason and senses would know: this decades long vampire soap opera is, indeed, 100% HOGWASH! Good night, kiddies; your feelings of disappointment will fade in time.