F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (1922) is widely considered to one of—if not the—best vampire movie ever made. It has a 97% approval rating on film review aggregator site, Rotten Tomatoes; it’s fourth place on Movie Review Query Engine’s “Cinema’s Best Vampire Movies“; and sits at the top of Flickchart’s “The Top 100 Vampire Films of All Time.”

The Internet Movie Database charts 333 connections to the film, collating versions, remakes, films it has been edited into, referenced in, featured in and spoofed. Its influence and power can not be underestimated. But for all that, have you actually seen it? Did it frighten you? After all, it’s supposed to be one of the scariest movies ever made.

The film’s reputation, the scholarly praise heaped on it, its pop culture appearance in books, comics and the like was what I had to work with when I first saw it many years ago. I remember taping (on VHS) when it screened on one of my local multicultural channels, SBS, so I could watch it later. I remember eagerly waiting to see it and when I did—I was disappointed. “What’s the big deal?” I thought. It wasn’t scary. At all. It was slow. Some bits—like the sped-up scene where the disguised vampire picks up Jonathan in the carriage—were just silly. This was supposed to be the best vampire movie ever made?

Despite that, I’m not saying it’s bad. Not bad in a Mama Dracula kinda way, just—it wasn’t what I expected it to be. I can understand its value from a cultural and historical perspective. There’s no question that Nosferatu is an important film. It’s clever, inventive, creative. But those things don’t necessarily make it an enjoyable or entertaining film, either. Or a scary one. That said, I’ve often wondered if I was missing something. Maybe I didn’t watch it “right”. When I studied Studio Arts in high school, my teacher advised me not to read anything about a movie before seeing it. That way, I could enjoy it on its own merits. To this day, I avoid reading much about films I want to see.

The Challenge

On July 16, I was talking about the film with Erin, mentioning that its star, Max Schreck’s surname, meant “Terror” in German and it was his real name. I asked her if she’d seen it. “Nope,” she said. That’s when it clicked. Someone who’d never seen the film. Someone who knew little about it. Of course—a chance for an unbiased review! Was I alone thinking it wasn’t all it’s cracked up to be? It was time to find out.

I framed it as a challenge, which it was, but set the ground rules from the start—read nothing about the film. Don’t research it, just watch it. Tell me what you think. After she did that, then I’d tell her what the challenge’s point was. Fortunately, she was up for it.

Her review was published on July 31. I titled it “A Virgin’s View on Nosferatu,” riffing on her throwaway, but perfectly astute line about me wanting “virgin eyes” for the review—her words, not mine! What caught me off guard, however, was how “inexperienced” she was in terms of her awareness of the film’s background; things I thought were common knowledge, but may actually speak more of my “experience.”

So, with that in mind, there were several points and observations she raised in her review, which I wanted to address—not just for the reader, but for Erin, too. I’m not saying that to rag on her. Far from it. If anything, it was fascinating to witness what “virgin eyes” can see.

Music

First off, Erin watched an English translation of the movie, which its opening credits reveal was “Acquired through the courtesy of La Cinémathèque Française” and posted by YouTube user, LuckyStrike502, seemingly obtained from Archive.org; the Internet Archive. Context is important here, because she was obviously relying mainly on the movie’s subtitles, which will become especially pertinent when we start delving into character names and the like. Her comments about the film’s sound threw me, though:

You gotta love the crackling dead sound in the beginning as the credits shakily make their way up the screen. The music in this film instantly caught my attention and is what stood out the most. Occasionally, I found myself tripping out on it and not paying attention to the characters.

The film is silent. Many scores have been written for it over time, including one by James Bernard (1925–2001)—so I’m not sure who composed this one. No credits are given. The original was by Hans Erdmann (1882–1942), though. The music on the version Erin watched does seem to differ from the original (not by much, admittedly), going by this snippet, a reconstruction of Erdmann’s score by musicologist, Gillian B. Anderson:

[su_youtube url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjSZ0dQV_pU” responsive=”yes”]

That said, if music, itself, was jarring to watching the movie, the score might’ve been irrelevant. It might even be Erdmann’s. Anyway, onto the next points.

Name Changes

Erin mentioned “Jonathan”, “Nina” and “Dracula” throughout her review—no harm, no foul, because those are the names the characters are given in the opening credits. However, they had different names in the original version of the film. “Jonathon” was “Hutter”; “Dracula” was “Orlok” and “Nina” was “Ellen”. Those name changes tie into some of her other observations:

The beginning credits indicate this movie is based on the novel written by Bram Stoker in 1897; however, I couldn’t say how close the adaptation is because I am currently reading the Broadview edition for the first time as well. The film appears to reference the same characters; just I am not sure on similarities between both versions. Jonathan seems to be flakier in the film and so does Nina, which we all know as Mina from the book. The name difference actually brings a question to mind. If the movie is based on the book why is the name changed? Also I noticed many of the cast have foreign names, so I am wondering where it was filmed? If the actors are no names then the budgets were kept pretty low.

I don’t wanna spoil the rest of the book for Erin, but there are a lot of similarities between the novel and the film—and that’s not a coincidence. You see, Nosferatu is often credited as the first cinematic adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel, Dracula (1897), but technically it wasn’t supposed to be—not legally, anyway. Rather than buy the rights to adapt Stoker’s novel from the Stoker estate, the filmmakers tweaked the the film’s details just enough—or so they thought—to avoid paying out. So, Count Dracula became “Graf Orlok,” Jonathan Harker became “Thomas Hutter”, London became Bremen and so on.

Unfortunately for them, the tweaks weren’t enough because—how do I put this lightly—Nosferatu is a fuckin’ obvious Dracula rip-off. Not passing similarities, either. A real estate sent to Transylvania to visit an (unknown to him) vampire count who wants to finalise property purchase in a major city? Imprisons the agent in his castle; arrives at the city by ship, wipes out the crew? Madman servant? Who were they trying to kid? Hutter is obviously Jonathan Harker, Ellen (or Nina as she’s renamed in that version) is Mina, Graf Orlok is Count Dracula.

In fact, the film’s title is even derived from a term featured in and popularised by Stoker’s novel, nosferatu, which has and has since become a synonym for vampire. It appears twice in Dracula and mentioned by Abraham Van Helsing each time. First, in the scene where the intrepid vampire hunters track vampire Lucy Westenra to her tomb:

Friend Arthur, if you had met that kiss which you know of before poor Lucy die, or again, last night when you open your arms to her, you would in time, when you had died, have become nosferatu, as they call it in Eastern europe, and would for all time make more of those Un-Deads that so have filled us with horror.

And again when, when they reconvene in John Seward’s study the following night: “The nosferatu do not die like the bee when he sting once. He is only stronger, and being stronger, have yet more power to work evil.”

Stoker popularised the term, but he didn’t invent it: he learned it from “Transylvanian Superstitions,” an article by Emily Gerard (1849–1905) featured in The Nineteenth Century magazine’s July 1885 issue. “More decidedly evil, however,” she wrote, “is the vampire, or nosferatu, in whom every Roumenian [Romanian] peasant believes as firmly as he does in heaven or hell.”

Due to the word’s obscurity, it was thought, until recently, that Gerard may have misheard or misidentified it—until I tracked down an article by an Austrian writer, pre-dating Gerard’s work by twenty years.

The movie’s “similarities” didn’t bypass Stoker’s widow, Florence Balcombe (1858–1937). After finding out about the film’s liberal use of her husband’s story, she hounded the British Incorporated Society of Authors to help take legal action against Nosferatu‘s production company, Prana-Film—and won. The court ordered all copies of the film destroyed and Prana-Film declared bankruptcy—Nosferatu was both their first and last movie.

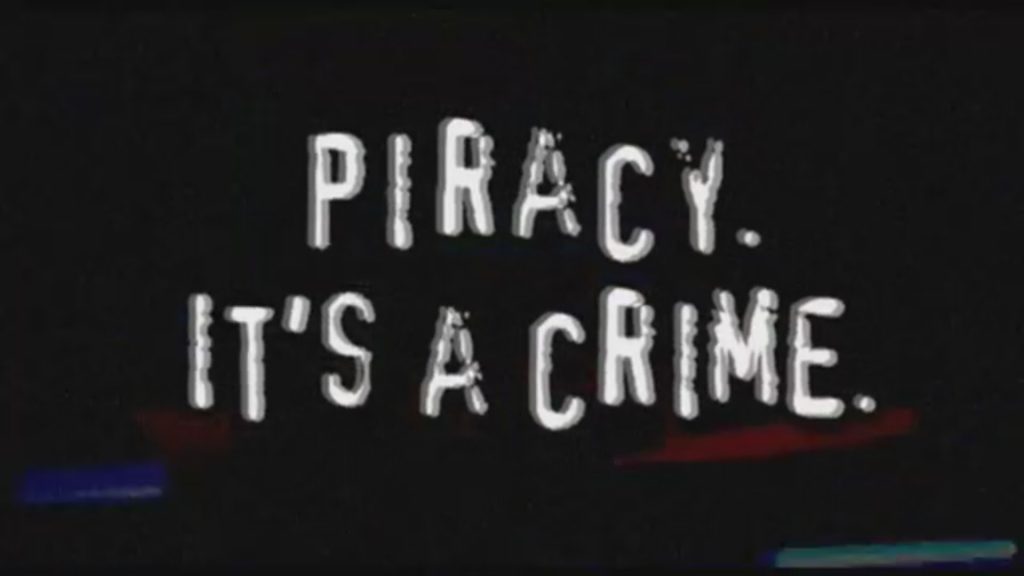

But hang on, if all copies were destroyed, how are we able to watch it on YouTube today? Well, despite the order, copies of the film were made and distributed elsewhere. As Phil Hall elaborates in his “Bootleg Files” article for Film Threat,

some prints were already in circulation throughout Europe, and the British court was unable to track them down and destroy them (the surviving prints wound up in France, out of the jurisdiction of the British legal system). The film eventually showed up in the U.S. in 1929, but its distribution was severely limited because silent movies were being ignored in favor of sound films. The American distributor, Film Arts Guild, went out of business shortly after the film was released, and “Nosferatu” was eventually doomed to public domain status.

After the novel’s copyright lapsed in the US in 1962, it was re-screened and, as noted by Plagiarism Today‘s Jonathan Bailey, it “slowly began to gather an audience in the U.S. and, by the 1960s, had earned a place as a horror classic.” Indeed, the Orlok was re-named “Dracula,” Hutter re-named “Jonathon” and so on. That whizzing sound? Florence Balcombe spinning in her grave.

In short, Nosferatu, the highly-influential, widely-praised film, only exists today because it was pirated over 90 years ago. Something to think about next time you watch one of those “You Wouldn’t Steal a Car!” anti-piracy videos at the start of DVDs—yeah, the ones with the stolen music.

For the record, the first official cinematic adaptation of Stoker’s novel—and even then, more like an adaptation of John L. Balderston’s rewrite of the Hamilton Deane theatrical adaptation of the novel—was Todd Browning’s Dracula (1931), the Universal movie that catapulted Bela Lugosi (1882–1956) into stardom, while simultaneously forever typecasting him as the Count.

Universal succeeded in securing the film rights from Florence where Prana-Film failed, yet it turns out they might not have needed to. According to David J. Skal, Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web of Dracula from Novel to Stage to Screen (New York: Norton, 1990):

due to a loophole in copyright law, Dracula was – and always had been – in the public domain in the United States. Although Stoker had been issued a copyright certificate in 1897, and his widow a renewed certificate in the 1920s, Stoker had never complied with the requirement that two copies of the work be deposited with the American copyright office. (180)

A tangled web, indeed. If you’re interested in the whole story, I recommend getting a copy of Skal’s book or the Faber and Faber revised paperback edition, published in 2004.

As to the cast’s names and location, well, their names are foreign because it was a German film with German actors. As noted, Orlok was played by Max Schreck, Thomas Hutter was played by Gustav von Wangenheim (1895–1975) and Ellen was played by Greta Schröder (1892–1967) and so on. The film’s original credits and intertitles were, of course, written in German, too.

The location shots, as Martin Votruba, writing for University of Pittsburgh’s Slovak Studies Program notes, were filmed in Slovakia, and take up “about 15% of the film’s runtime.”

Has It Been Remade?

Erin also noted the following in her review: “I am assuming they have remade this movie because they redo everything, but thanks to Anthony I have no idea and I am just speculating. If there is another version I would be interested to see how it has transformed over the years.”

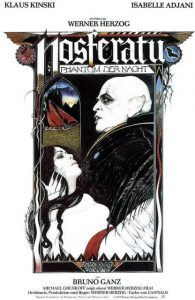

Well, Erin, looks like you’ve set yourself up for another challenge! Yes, it was remade—as Nosferatu: Phantom der Nachet (1979), directed by Werner Herzog (b. 1942). That version features no “Orlok” pretences: the vampire count is named Dracula (played by Klaus Kinski [1926–1991]).

Hutter is back to being Jonathan Harker (Bruno Ganz [b. 1941]) and Ellen/Nina/Mina—well, she’s inexplicably renamed Lucy Harker (Isabelle Adjani [b. 1955]). Mina just can’t catch a break with Nosferatu.

In the spirit of the challenge, though, I’ll say precious little about Herzog’s version here, except to mention that there are two versions of the film: the German original and the English language version commissioned by 20th Century Fox and retitled Nosferatu the Vampyre. Same actors, same film. As Wikipedia notes,

Scenes with dialogue were filmed twice, in German and in English, meaning that the actor’s own voices (as opposed to dubbed dialogue by voice actors) could be included in the English version of the film. However, many consider the performances in the German-language version to be superior, as Kinski and Ganz could act more confidently in their native language.

Vampire film reviewer, Andy Boylan, alluded to another Nosferatu remake I wasn’t aware of, one “badly remade by a budget filmmaker” in his comment on Erin’s article. He then shared a link to his review of David R. Williams’ Red Scream Nosferatu (2009), which begins by mentioning that the film presents itself as “an edgy, blood-drenched revisioning of the classic original vampire film”, but wraps up with this:

Cruel as I am in my conclusions; this touched, perhaps even violated, a classic piece of cinema and most of the touches were the fumbling of a clumsy virgin, only in the one mentioned section did the virgin become Casanova. My advice, take the bride section and make something new and original with it. 3 out of 10.

Yeah, bugger that. Come to think of it, it’s surprising more people haven’t given it a crack, considering Nosferatu is public domain and, as Erin noted, “because they redo everything”. Good point—but don’t mistake that for an invitation. There’s enough bloody remakes as it is.

As it happens, though, a sort-of sequel was released in 1988. It’s an Italian film directed by Augusto Caminito (b. 1939) called Nosferatu a Venezia—also known as Vampire in Venice—and even stars Klaus Kinski as Count Dracula. But as Wikipedia notes,

The film is an in-name-only sequel to Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre, although its almost completely unrelated with Herzog’s version of the Nosferatu story only with Kinski returning to reprise his loosely connected role.

Death by Sunlight

Here’s how Erin describes the use of a book in the film, to eventually destroy Orlok:

It basically gave her instructions with the following excerpt, “Only a woman can break his frightful spell- a woman pure in heart- who will offer her blood freely to Nosferatu and will keep the vampire by her side until after the cock has crowed.” Her plan worked and Dracula teleported again into the beyond, leaving only a little trail of smoke behind, indicating he had perished.

The indication is correct. In fact, that scene kicked off a trope so popular, it’s often mistaken for actual folklore: the notion that vampires can be harmed or “killed” by sunlight. Yet it’s not a folkloric trait, at all (despite their generally nocturnal activities): it was invented by the movie’s screenwriter, Henrik Galeen (1881–1949).

Soon enough, the idea weaved its way into other movies. The trope features in two Universal movies; Son of Dracula (1943) and House of Dracula (1945). Hammer Films got into the act, too: the first movie in their Dracula series, Dracula (1958)—better known by its American title, Horror of Dracula—famously ends with Van Helsing forcing the vampire count into sunlight with an improvised cross. Jonathan Bailey elaborates on the impact this concept had for vampires:

The biggest change was the ending of the movie. In Nosferatu, Count Orlok is burned up by the sunlight. However, in Bram Stoker’s version, sunlight was harmless to vampires, it just weakened them slightly.

However, this idea of vampires being killed by sunlight has been used over and over again in various movies, including many carrying the Dracula name. The theme has become so common that, in the more-accurate 1992 movie retelling of the book, a narrator has to explain why Dracula can walk in the daylight for a crucial scene.

It’s a popular literary trope, too. In the popular “Vampire Chronicles” series by Anne Rice (b. 1941), death by sunlight is one of two ways vampires can be destroyed: the other’s fire.

Outside movies and books, the trope’s also spilled into real life, too. Certain medical conditions, like porphyria—in which sufferers experience severe reactions to sunlight exposure—have been used to explain the origin of the vampire myth, going back to the “Middle Ages”, despite the trope’s grounding in cinema history, not folkloric history.

Meanwhile, many members of the Vampire Community, people who identify as vampires, often mention bad reactions to sunlight as a symptom of their condition, likely not realising that the vampiric associations originate from Galeen’s imagination—and perhaps without realising that they’re more likely suffering from sun allergies, a treatable medical condition, not related to vampirism at all. That is the power of Nosferatu.

Erin’s (Tiny) Error

During the course of her review, Erin made a little mistake I didn’t want to correct, to uphold the purity of her review. She mentioned,

When Jonathan stayed overnight in the inn on this journey to the count’s castle he found “The Book of the Vampire,” from 1443. He checks it out and laughs it off, thinking it’s ridiculous. Yet he does end up bringing it with him to the castle and even Nina finds it after he returns home. It is like the entire plot depends on this random mini book that just happened to find it’s way into his luggage for his entire journey by accident. Hell the only reason Nina managed to kill the vampire was because she read the damn thing, when she wasn’t supposed to.

Two things. First, in the movie version she watched, it’s called The Book of the Vampires, not “The Book of the Vampire”. Second, it’s not dated 1443, but one of its pages says “and it was in 1443 that the first Nosferatu was born.”

As a side note, readers familiar with Dracula will recognise the book as an obvious stand-in for Jonathan Harker’s diary—yet another plot point, swiped! Those guys really had no shame.

Conclusion

Erin was a real trouper. She did great, too. Though she didn’t have the highest regard for the film, she’s not the only one. I know there’s others out there. In fact, Phil Hall, who I quoted from earlier, also had this to say about the film in the same article:

I hate to be the sourpuss in the Halloween pumpkin patch, but I never liked “Nosferatu.” I can appreciate its historic importance as the world’s first vampire film, and I acknowledge that director F.W. Murnau created an artistically impressive production. But I could never achieve a genuine emotional connection with “Nosferatu.” I tried again the other week while doing the research for this article – but I fell asleep watching the movie.

In my personal opinion, nostalgia and critical praise have been as integral to the film’s success as much as its ability to frighten and inspire. It seems almost like a peer pressure thing: everyone else says it’s great, so I better say it, too! Maybe. But that’s just my view. If you’ve seen the film, watch it again. See if you have the same thoughts about it as when you first watched it. If you never have, view it through your own “virgin eyes”—see what you think. Ask yourself, “What’s so special about this movie?”

The funny thing is, when I gave Erin some backstory to the movie on July 28 (specifically the bit about Stoker’s widow going after the filmmakers) after she finished her review, she said: “Fuck seriously? So an all time classic is a rip off?” and “now this makes it more interesting lol“

Perhaps that’s all it takes: a little backstory. Eric D. Snider asked the same question I did, long before I started this thing: “What’s the Big Deal?” Context, apparently. I’ll give it that, but even then, it’s a subjective thing, isn’t t? Does a film’s backstory make it a better film by default? You be the judge.

2 comments

Comments are closed.