As anyone who has read Bram Stoker Dracula (1897) will know, Whitby on the North Yorkshire coast has a major claim to literary fame, being the place that Stoker chose as the location for chapters six, seven and eight of his famous novel.

It was also in the Whitby Subscription Library that he found William Wilkinson’s An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia (1820); an old history book about a region of Eastern Europe which is now modern-day Romania.

On page nineteen he came across a fairly unremarkable footnote about a local voivode who had been given the title of “Dracula”:

Dracula in the Wallachian language means Devil. The Wallachians were, at that time, as they are at present, used to give this as a surname to any person who rendered himself conspicuous either by courage, cruel actions, or cunning.

This was a key moment for the novel. It was so important, this single page in Wilkinson’s book has even been called “Count Dracula’s birth certificate.”

Travels to Whitby

I’ve always been fascinated by Dracula. When I went to Whitby for the first time in 1994 I fell in love with the town and its Victorian atmosphere. Now, over two decades later, I try to spend a few days there, at least once a year.

Sadly, the United Kingdom is also famous for having bad weather and it was on a particularly cold, wet and windy Monday afternoon on May 30, 2016, that I found myself in Whitby Museum looking at the famous fossil collection.

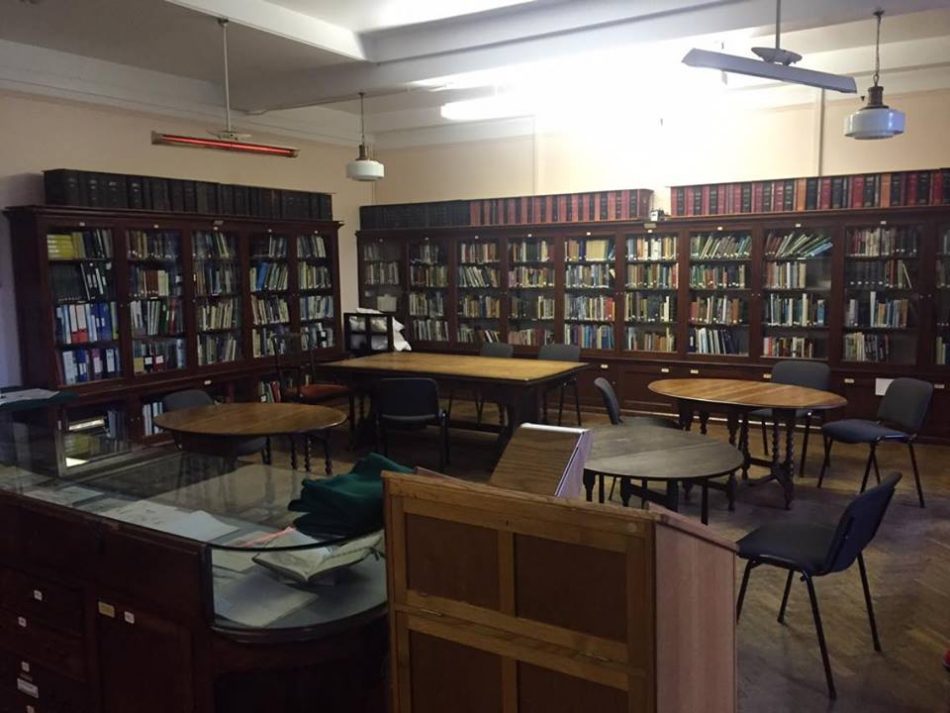

Tucked away in the corner of the building I spotted the doors to the Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society and suddenly remembered that this is where Stoker read Wilkinson’s book and saw that famous footnote. Wouldn’t it be amazing if the book was still there and I was able to hold it for myself for in my own hands? I decided to investigate.

The Dracula/Whitby Connection

Whitby itself is pretty much like any other seaside resort in the United Kingdom. As well as having a fairly nice beach, it has all the other usual attractions such as donkey rides, amusement arcades, gift shops and, of course our national dish, fish and chips (and very good ones they are too!). If that was all there was to Whitby it would indeed be just another coastal town, but its connection with Dracula gives it an extra special dimension.

Strangely, though, I’ve always had the feeling that, for many of the locals in Whitby, this connection has been a bit of a mixed blessing. On the one hand it brings many tourists and revenue to the town, particularly during the annual Goth Weekend while, at the same time, they find it a little tedious when some people believe that Dracula was a real person, the events in the novel actually happened and that the Count is buried up in St. Mary’s Churchyard.

Fortunately, Whitby has changed very little since Stoker visited in the late nineteenth century. At the beginning of chapter six, he provides a very clear description of the town as seen by Mina while she sits on her “favourite seat” in St. Mary’s Churchyard up on the East Cliff. Based on this description I believe it is still possible to see everything Mina saw including the harbour and Tate Hill Sands where the Demeter mysteriously runs aground during the great storm and where, in the form of a big black dog, Count Dracula jumps ashore.

To the left of Mina’s seat are the famous 199 abbey steps that Dracula runs up, and directly behind it is the graveyard where he attacks Lucy for the first time.

It’s an amazing feeling sitting up there during the day but at night, with heavy seas breaking over the harbour walls and an eerie, dank mist rolling in off the sea, you almost feel like you could be a character in the novel. It is an unforgettable, magically spooky experience.

Of course, when Stoker came to Whitby for his holiday in the Summer of 1890 these scenes had yet to be written. According to his working notes for Dracula, he had started mapping out his ideas for the book back in London a few months earlier.

During those early stages the novel was very different to the one we know now. He initially wanted to set the opening chapters in Styria, a province in Austria, but it was only after reading Emily Gerard’s article for Nineteenth Century magazine, “Transylvanian Superstitions” (July 1885) in which she outlines much of the region’s folklore surrounding vampires, that Bram decided it would be a much better location for the Count’s mountain top home.

This interest in Eastern Europe may also explain why he chose to flick through Wilkinson’s book in Whitby library. He must have been impressed with what he saw on page nineteen because he copied it into his notebook. Reading that name proved to be a pivotal moment for Stoker; he went back through his notes, crossed out anywhere he had written the name “Wampyr” and replaced it with “Dracula.”

My Search for Wilkinson’s Book

I first became aware of Wilkinson’s book after reading about it Peter Haining’s The Dracula Scrapbook (1992) while conducting research for a university project: a short film called Bram Stoker’s Whitby. At that time, I was studying for a degree in European Audio Visual Production at Humberside University a few miles further down the Yorkshire coast in Hull.

Realising I was only about an hour’s drive from Whitby I had decided to make a documentary about the town and its connection to the novel. In those days I hadn’t even thought about looking for Wilkinson’s book and it wasn’t until I had made several other visits to the town that I became curious about what might have happened to this important piece of literary history.

One evening, a few years ago, I did a “Dracula Walk” with Whitby’s very own storyteller, Harry Collett. During our stroll around the town he recounted various vampiric tales as well as pointing out places associated with Bram Stoker’s 1890 holiday. One of our stops was a three story building on Pier Road which, Harry informed us, was the very place where Stoker had read Wilkinson’s book.

In Stoker’s day, the ground floor of the building had been the town’s bathhouse while, upstairs housed the museum and library. Today nothing of the museum and library remain. The ground floor is the Quayside fish and chip restaurant and the first floor is now a bar.

In April 2012 I attended the Bram Stoker Centenary Conference at the University of Hull and met David Pybus, a Whitby-based researcher. While we were chatting about Wilkinson’s book and the the Whitby Museum and Subscription Library, he informed me that the museum re-located in 1931 to a new building just up the road in Pannett Park and the library changed its name to the Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society.

So this brings us right back up to date with my cold, wet and windy day looking at ammonites in Whitby Museum on May 30, 2016. Entry to the Literary and Philosophical Society is limited to certain times but, unfortunately, I was too late for that particular day. Lucky for me that the people of Whitby are kind folk and allowed me in to have a quick chat with a member of staff called Fiona who was still in there.

I explained to Fiona what I was looking for and was met with a rather pained “oh no, not another Dracula nut” which quickly softened once I further clarified that I was actually looking for a very real history book and not the location of Dracula’s grave or some equally fictional folly.

Fiona told me that, unfortunately, she was not the best person to speak to and all that she could offer me for now was a quick look through their card index. Sadly, this proved to be fruitless.

Fiona informed me that this didn’t necessarily mean they didn’t have the book and that I should leave a note for her colleague and return the following morning.

When I went back the next day, the actual librarian confirmed that Wilkinson’s book was not in their collection and, moreover, never had been. She added that when the library moved, someone went down to the old building and hand picked which books would be moved over. Unfortunately, Wilkinson’s book was not one of them. When I asked if she knew what might have happened to the rest of the books she replied “they probably found their way to a dump somewhere.”

I was disappointed to say the least, especially when I thought of this iconic piece of history rotting away in landfill. Rest, assured though, this will not be not the end of my search. If, somewhere, a record exists of what actually happened to the books that weren’t moved to the new building, I will endeavour to find it.

To console myself I decided to go for a pint at my favourite pub in Whitby, The Black Horse Inn on Church Street, after which I climbed the 199 steps up to St Mary’s Church for a walk through the graveyard. I’m not great believer in fate but I am almost prepared to change my view, for right there, written on one of the tombstones, was the name William Wilkinson!

It was clearly a different person; according to his gravestone he had been a “constable of Whitby Strand” and not the “late British consul resident at Bukorest [Bucharest]” as stated on the title page of An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, but it was still a very spooky coincidence none the less. Perhaps it was even a message from beyond the grave telling me to continue my search?

Notes:

- “Count Dracula’s birth certificate”: “Dracula,” Nightmare: The Birth of Victorian Horror, BBC (1996).

- the Count is buried up in St. Mary’s Churchyard: “St. Mary’s Churchyard” is the colloquial name given to the churchyard attached to St. Mary the Virgin, Whitby, an Anglican parish church on the East Cliff. See itinerary.

- Based on this description I believe it is still possible to see everything Mina saw: The location of Lucy and Mina’s favourite seat is based upon my own investigations using the description of the view of Whitby at the beginning of chapter six. Bram Stoker, Dracula (London: Arrow Press, 1979), 62. From this vantage point, it is possible to see everything Mina describes in the text.

- he had started mapping out his ideas for the book back in London a few months earlier: Stoker gives the date “8/3/90” – 8 March 1890. Bram Stoker, Bram Stoker’s Notes for Dracula: A Facsimile Edition, annotated and transcribed by Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2008), 16.

- Bram decided it would be a much better location for the Count’s mountain top home: Elizabeth Miller, interview with the author, ca. May 9, 2009.

- He must have been impressed with what he saw on page nineteen: Stoker, Bram Stoker’s Notes for Dracula, 244. Stoker emphasised “Dracula” and “Devil” in his transcription of Wilkinson’s footnote by capitalising both words.

- I first became aware of Wilkinson’s book: Peter Haining, The Dracula Scrapbook (London: Chancellor Press, 1992), 33. Not to be confused with Haining’s 1976 book of the same name, this is the revised edition of Haining’s The Dracula Centenary Book (1987).

- It was clearly a different person: The author of An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia died in Paris on August 23, 1836.

Itinerary:

- Whitby Museum: Pannett Park, Whitby, North Yorkshire. http://www.whitbymuseum.org.uk/.

- St. Mary the Virgin, Whitby: Abbey Plain, East Cliff, Whitby. https://www.achurchnearyou.com/whitby-st-mary/.

- Whitby’s 199 Steps: 199 Steps, Whitby. http://www.whitbyonline.co.uk/whitby/whitby-leisure/199-steps/.

- Quayside: 7 Pier Road, Whitby. http://www.quaysidewhitby.co.uk/.

- The Black Horse Inn: 91 Church Street, Whitby. http://www.the-black-horse.com/.

Leonard Lee is a freelance lighting cameraman. Visit his website here: http://www.leonardlee.co.uk/.

While I know it’s not /thee/ copy that Leonard is looking for, the book, An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, is available for free in digital format on Google Books, as well as several other sites. As always, quality does vary widely with these digitizations depending on the care taken at the time. But yeah. It’s not the copy that Bram thumbed through, but it’s also good to know that enough copies have survived to be digitized.

Hello there, thanks for the info. I’ve also seen copies for sale from antique book sellers for around the £500/ $800 mark. I might consider paying that for the one from Whitby but not just any old copy.